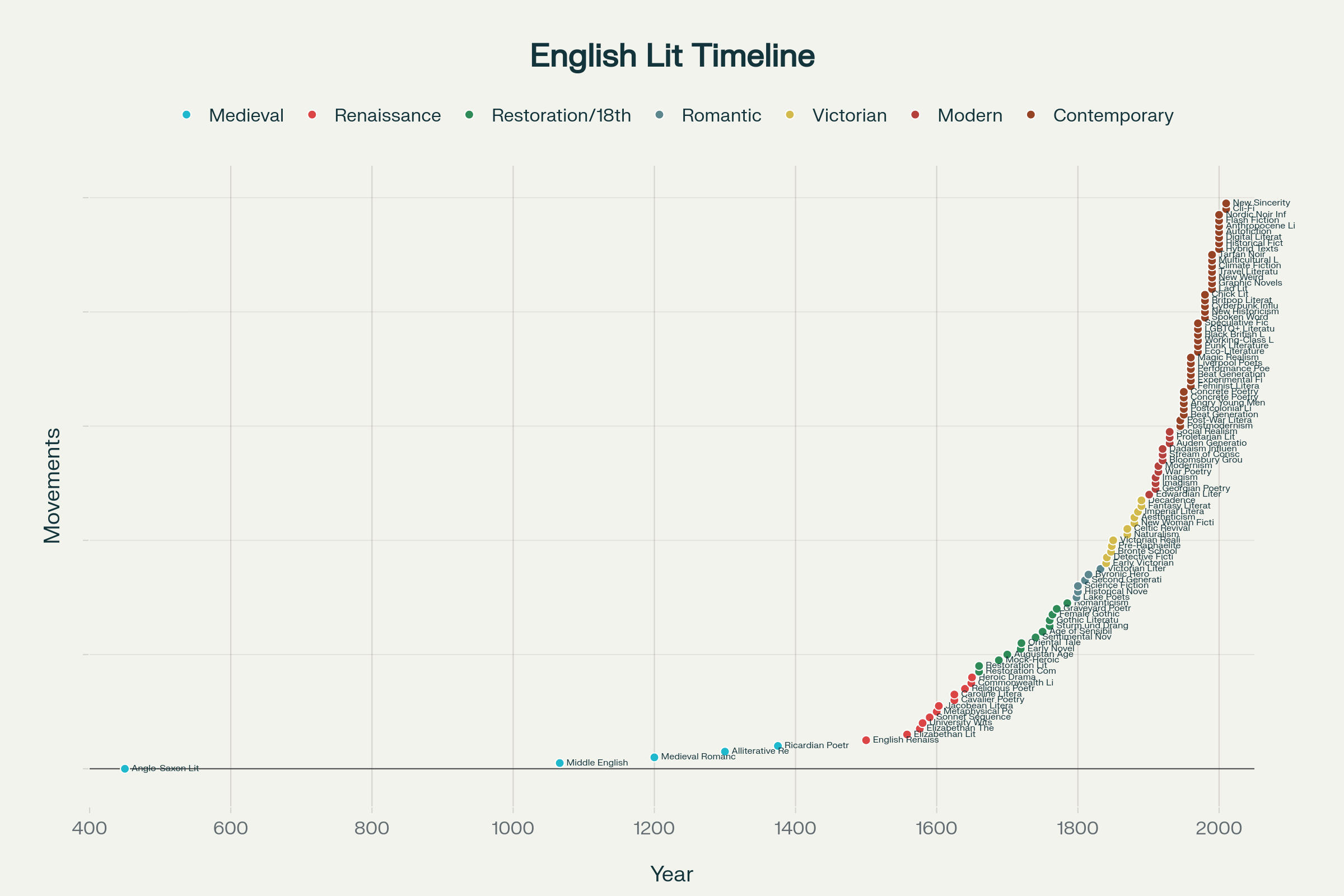

100 Most Important Literary Movements in English History

The rich tapestry of English literature spans over fifteen centuries, encompassing a remarkable diversity of movements, styles, and voices that have shaped not only the literary canon but also cultural consciousness across the globe. From the heroic verses of Anglo-Saxon poetry to the digital narratives of the twenty-first century, English literary movements reflect the continuous evolution of human expression, societal values, and artistic innovation. This comprehensive exploration examines one hundred of the most significant literary movements that have defined English literature, tracing their historical contexts, key characteristics, major works, and enduring influences on subsequent generations of writers and readers.

Timeline of 100 Most Important Literary Movements in English History (450-2025 CE)

The Movements (1–100)

- Old English (Anglo-Saxon) Poetry (c. 700–1066)

Alliterative verse; heroic ethos; Christian-pagan blend. Beowulf, “The Wanderer.” Themes: fate, exile, courage. Technique: caesura, kenning. - Anglo-Norman & Middle English (1066–1400)

Romance, allegory, estates satire. Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales; Langland’s Piers Plowman. Themes: social order, morality. Technique: frame narrative.

“And gladly wolde he lerne and gladly teche.” — Chaucer

- Mystical & Devotional Prose (c. 1370–1420)

Julian of Norwich, The Cloud of Unknowing. Themes: contemplation, divine love. Technique: paradox, metaphor. - Humanism & Tudor Renaissance (c. 1485–1603)

Rediscovery of classical rhetoric. Sir Thomas More, Sidney, Spenser. Themes: virtue, order. Technique: sonnet sequence, allegory. - Elizabethan Drama (c. 1580–1610)

Public theatre explosion. Shakespeare, Marlowe, Kyd. Themes: power, identity, fate. Technique: blank verse, soliloquy.

“The play’s the thing.” — Hamlet

- Metaphysical Poetry (c. 1590–1650)

Bold conceits, wit, sacred/profane tension. John Donne, George Herbert, Marvell. Themes: love, faith, time. Technique: paradox, metaphysical conceit.

“Batter my heart, three-person’d God.” — Donne

- Cavalier Poets (c. 1620–1650)

Courtly grace; “seize the day.” Herrick, Suckling, Lovelace. Themes: loyalty, pleasure. Technique: lyrical polish. - Puritan/Commonwealth Writing (c. 1640–1660)

Plain style, ethical seriousness. Milton’s Areopagitica and Paradise Lost. Themes: liberty, conscience, fall and redemption. Technique: grand epic blank verse.

“They also serve who only stand and wait.” — Milton

- Restoration Drama & Satire (1660–1700)

Comedies of manners; libertine wit. Wycherley, Congreve, Aphra Behn. Themes: reputation, desire. Technique: repartee, dramatic irony. - Augustan/Neoclassicism (c. 1700–1745)

Order, decorum, balance. Alexander Pope, Swift, Addison & Steele. Themes: reason vs. folly. Technique: heroic couplets, mock-epic.

“To err is human; to forgive, divine.” — Pope

- Graveyard School (c. 1740–1760)

Meditations on mortality. Thomas Gray, Edward Young. Themes: death, transience. Technique: elegy. - Pre-Romanticism (c. 1750–1790)

Feeling and nature intensify. Ossian (Macpherson), Cowper, Burns. Themes: rural life, sensibility. - Gothic (c. 1764–1820; revivals later)

Sublime terror, haunted spaces. Walpole, Radcliffe, Mary Shelley. Themes: repression, otherness. Technique: suspense, doubling. - Romanticism (c. 1789–1832)

Imagination, nature, individual spirit. Wordsworth, Coleridge, Byron, Shelley, Keats, Blake. Techniques: lyric “I,” symbolism, organic form.

“Poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings.” — Wordsworth

- Lake Poets (c. 1798–1808)

Wordsworth/Coleridge/Southey in the Lakes. Themes: memory, nature; Technique: conversational blank verse. - Regional Romanticism (Scottish/Irish) (c. 1800–1830)

Scott, Moore, Mangan. Themes: nation, folklore. Technique: ballad revival. - Silver-Fork & Regency Novel (c. 1820–1837)

High-society manners. Bulwer-Lytton, Disraeli. Themes: class, fashion. - Victorian Realism (1837–1901)

Social panorama; moral inquiry. Dickens, George Eliot, Trollope, Gaskell. Techniques: free indirect style, serialized plotting.

“It is a truth commonly acknowledged…” (Austen is late Georgian/Regency but shapes Victorian realism’s psychology).

- Victorian Dramatic Monologue (c. 1830–1890)

Browning, Tennyson, Christina Rossetti. Themes: voice, mask, desire. Technique: persona, irony. - Pre-Raphaelite Aesthetic (c. 1848–1880)

Medievalism, lush imagery. D. G. Rossetti, Morris, Swinburne. Themes: beauty, artifice. Technique: color symbolism. - Sensation Fiction (c. 1860s)

Crime and scandal in the home. Wilkie Collins, Braddon. Themes: identity, secrecy. Technique: cliffhangers. - Industrial/Condition-of-England Novel (c. 1840–1870)

Gaskell, Disraeli. Themes: labor, reform. Technique: documentary realism. - Nonsense & Children’s Literature Renaissance (c. 1840–1900)

Edward Lear, Lewis Carroll. Themes: logic play, imagination. Technique: neologism. - Scientific Romance & Early SF (c. 1860–1910)

H. G. Wells, Jules Verne (cross-channel influence). Themes: progress, ethics. Technique: extrapolation. - Aestheticism & Decadence (c. 1880–1900)

Art for art’s sake. Wilde, Beardsley. Themes: beauty, performance, moral ambiguity. Technique: paradox, epigram.

“All art is quite useless.” — Wilde

- Late-Victorian Gothic/Fin-de-Siècle (c. 1880–1900)

Stevenson, Stoker, Le Fanu. Themes: duality, degeneration. Technique: fragmented narrative. - Irish Literary Revival (c. 1890–1920)

Yeats, Lady Gregory, Synge; Abbey Theatre. Themes: myth, nationhood. Technique: symbolism.

“Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold.” — Yeats

- Georgian Poetry (c. 1910–1922)

Pastoral lyricism. Masefield, de la Mare, Housman. Counterpoint to Modernism. - War Poetry (WWI) (1914–1918)

Owen, Sassoon, Rosenberg. Themes: pity of war, trauma. Technique: half-rhyme, irony.

“The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est.” — Owen

- Modernism (c. 1900–1945)

Fragmentation, mythic method, stream of consciousness. T. S. Eliot, Joyce, Woolf, Pound. Themes: alienation, time, perception.

“In my beginning is my end.” — Eliot

- Imagism (c. 1909–1917)

Direct treatment of the “thing.” Pound, H. D., Aldington. Technique: precision, free verse. - Vorticism (c. 1914–1915)

Short-lived avant-garde. Wyndham Lewis, Pound. Technique: energy, angular imagery. - Dada & Surrealism in English (1916–1930s)

Anti-art shock; dream logic. Mina Loy, David Gascoyne. Technique: collage, automatic writing. - Harlem Renaissance (1920s)

In English but US-rooted; global influence. Langston Hughes, Hurston. Themes: Black modernity. Technique: jazz rhythms.

“I, too, am America.” — Hughes

- Bloomsbury Group (c. 1905–1935)

Woolf, Forster, Strachey. Themes: personal liberty, art and ethics. Technique: interiority. - Theatrical Realism & Naturalism (1890–1930)

G. B. Shaw, Granville Barker. Themes: social critique. Technique: problem play. - Documentary & Mass-Observation (1930s–40s)

Reportage style in prose/poetry. Orwell, Auden (early). Themes: class, war, truth. - The Auden Generation (c. 1930s)

Auden, Spender, MacNeice. Themes: politics, anxiety. Technique: rhetorical control. - Middlebrow & Domestic Fiction (1920–1950)

E. M. Delafield, Elizabeth Bowen. Themes: class, gender, homefront. - Regional Realism (20th-century Britain)

Lewis Grassic Gibbon, D. H. Lawrence. Themes: landscape, sexuality. Technique: dialect. - Absurdist Drama (Theatre of the Absurd) (1950s–60s)

Beckett, Pinter, Ionesco (in English). Themes: meaninglessness, routine. Technique: silence, circularity.

“Nothing to be done.” — Waiting for Godot

- Angry Young Men (1950s)

John Osborne, Kingsley Amis, Alan Sillitoe. Themes: class resentment. Technique: abrasive realism. - The Movement (UK Poetry, 1950s)

Larkin, Amis, Davie. Themes: restraint, skepticism. Technique: regular meters, irony. - Confessional Poetry (1950s–60s)

Sylvia Plath, Robert Lowell, Anne Sexton. Themes: self, illness, family. Technique: stark imagery, free verse.

“Out of the ash I rise…” — Plath

- Beat Generation (1950s–60s)

Ginsberg, Kerouac (US, but strong impact in UK/India). Themes: freedom, spirituality. Technique: breath-based lines. - Black Mountain Poets (1950s)

Projective verse. Olson, Creeley, Levertov. Technique: open form, composition by field. - Deep Image Poetry (1960s)

Robert Bly, James Wright. Technique: archetypal symbolism, dream logic. - Postcolonial Anglophone Beginnings (1947–1970s)

R. K. Narayan, Mulk Raj Anand, Chinua Achebe, Wole Soyinka, Nadine Gordimer. Themes: empire, hybridity. Technique: code-switching. - Caribbean & Black Atlantic Literature (1950s–present)

Derek Walcott, V. S. Naipaul, George Lamming. Themes: creolization, memory. - African Anglophone Modernism (1950s–present)

Achebe, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o (later in English), Bessie Head. Themes: tradition/modernity. - Commonwealth Literature (1960s–80s)

Umbrella term for English writing beyond Britain/US. Themes: decolonization, voice. - Feminist Writing, Second Wave (1960s–80s)

Angela Carter, Atwood, Doris Lessing, Amitav Ghosh (gendered power in broader postcolonial frames). Techniques: revisionary myth, satire. - Black British Literature (1970s–present)

Linton Kwesi Johnson, Zadie Smith, Andrea Levy. Themes: diaspora, identity. Technique: dub poetry, multicultural realism. - Asian British Writing (1970s–present)

Salman Rushdie, Hanif Kureishi, Monica Ali. Themes: migration, hybridity. Technique: magic realism, irony. - Postmodernism (c. 1960–2000)

Play, parody, metafiction. Pynchon (US), Calvino (influence), John Fowles, Julian Barnes, A. S. Byatt. Technique: unreliable narrators, pastiche. - Magic Realism in English (1970s–present)

Rushdie, Okri, Garcia Marquez influence. Themes: history’s ghosts. Technique: matter-of-fact marvels. - New Journalism & Creative Nonfiction (1960s–present)

Joan Didion, Truman Capote, Ryszard Kapuściński (in translation influence), John McPhee. Technique: scene, persona. - Campus Novel Wave (1950s–present)

Kingsley Amis, David Lodge, Zadie Smith. Themes: academia, satire. - Experimental/Concrete Poetry (1950s–present)

Visual layout as meaning. Ian Hamilton Finlay, Dom Sylvester Houédard. - Language Poetry (L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E) (1970s–80s)

Charles Bernstein, Lyn Hejinian. Themes: critique of voice. Technique: fragmentation, parataxis. - New Formalism (1980s–present)

Return to meter/rhyme. Dana Gioia, Marilyn Hacker. Technique: sonnet revival. - Minimalism (1970s–90s)

Spare prose. Raymond Carver, Amy Hempel. Themes: alienation. Technique: understatement. - Dirty Realism (1980s–90s)

Working-class grit. Carver, Richard Ford. Technique: plain style. - Historiographic Metafiction (1980s–2000s)

Byatt, Barnes, Rushdie, Peter Carey. Themes: history as narrative. Technique: intertext. - Neo-Victorian Fiction (1990s–present)

Sarah Waters, Michael Faber. Themes: gender, empire revisited. - The New Puritans (UK, 2000s)

Manifesto for pared-down realism. Nicholas Blincoe, Matt Thorne. - Grime/Urban British Fiction (2000s–present)

Charlie Brinkhurst-Cuff (non-fiction edit), Irvine Welsh (Scottish urban; earlier). Themes: subculture, slang. - Tartan Noir (1990s–present)

Scottish crime. Ian Rankin, Val McDermid. Themes: policing, morality. - Nordic Noir in English Translation (2000s–present)

Influence on UK crime writing. Themes: social darkness. - Domestic Noir (2010s–present)

Gillian Flynn, Paula Hawkins. Themes: marriage, gaslighting. Technique: unreliable narration. - Weird Fiction & the New Weird (1990s–present)

China Miéville, Jeff VanderMeer. Themes: uncanny ecologies. Technique: genre-blend. - Speculative Climate Fiction (Cli-Fi) (2000s–present)

Margaret Atwood, Kim Stanley Robinson, Amitav Ghosh. Themes: Anthropocene, ethics. - Solarpunk (2010s–present)

Optimistic ecotech futures. Anthologies; Becky Chambers adjacency. Themes: sustainability. - Cyberpunk (1980s–present)

William Gibson, Neal Stephenson. Themes: high-tech/low-life. Technique: neologism, noir tone. - Steampunk (1990s–present)

Victorian tech reimagined. China Miéville, Gail Carriger. Themes: retro-futurism. - Biopunk/Body Horror (1990s–present)

Biotech anxieties. Jeff VanderMeer, Ling Ma (pandemic satire). Themes: contagion, identity. - Afrofuturism in English (1990s–present)

Nnedi Okorafor, Samuel R. Delany. Themes: technology, diaspora. - Indigenous Anglophone Resurgence (1990s–present)

Leslie Marmon Silko, Natalie Diaz. Themes: land, sovereignty. - South Asian Anglophone Modernism (1930s–60s)

R. K. Narayan, Mulk Raj Anand, Raja Rao. Themes: village/modernity. - Partition Literature (1947–present)

Saadat Hasan Manto (Urdu; in translation influence), Khushwant Singh, Bapsi Sidhwa, Amitav Ghosh. Themes: displacement, memory. - Indian English Postmodern & Magic Realism (1980s–present)

Rushdie, Arundhati Roy, Kiran Desai. Themes: nation, hybridity. - Dalit Writing in English/Translation (1990s–present)

Omprakash Valmiki (trans.), Bama (trans.), Rohith Vemula’s letters (non-fiction). Themes: caste, dignity. - Diasporic & Immigrant Narratives (1980s–present)

Jhumpa Lahiri, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. Themes: home, belonging. - Queer Literature (1970s–present)

E. M. Forster (earlier, posthumous Maurice), Alan Hollinghurst, Jeannette Winterson. Themes: identity, desire. - New Nature Writing (2000s–present)

Robert Macfarlane, Kathleen Jamie. Themes: ecology, place. Technique: lyrical nonfiction. - Travel Writing Renaissance (1980s–present)

Bruce Chatwin, Pico Iyer. Themes: mobility, culture. - Graphic Novel/Comics in English Literary Discourse (1980s–present)

Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman. Themes: myth, memory. Technique: multimodal symbolism. - Spoken-Word & Slam Poetry (1990s–present)

Performance-driven poetics. Kate Tempest (Kae Tempest), Lemn Sissay. Technique: voice, rhythm. - Flash Fiction & Microfiction (1990s–present)

Lydia Davis, Etgar Keret (translational influence). Themes: epiphany. Technique: compression. - Autofiction (2000s–present)

Self as fiction. Sheila Heti, Rachel Cusk. Themes: authorship, authenticity. - Trauma Narratives (1990s–present)

Memory and testimony. Pat Barker, Kazuo Ishiguro. Technique: unreliable memory. - Pandemic Literature (21st-century waves)

From Emily St. John Mandel to essays of Zadie Smith. Themes: contagion, society. - #MeToo-Era Feminist Fiction (2017–present)

Bernardine Evaristo, Sally Rooney (adjacent). Themes: consent, power. - Contemporary Gothic (2000s–present)

Sarah Waters, Andrew Michael Hurley. Themes: hauntings of history. - Holocaust & Genocide Literature in English (post-1945)

Primo Levi (trans.), Anne Michaels. Themes: memory, ethics. - New Sincerity (2000s–present)

Post-irony candor. David Foster Wallace (essay legacy), Ocean Vuong (lyric sincerity). Technique: earnest voice. - Metafiction & Self-Reflexive Revival (2000s–present)

Paul Auster, Ali Smith. Technique: narrative loop, direct address. - Digital Literature & Hypertext (1990s–present)

From Storyspace to Twine. Themes: reader agency. Technique: hyperlink structure. - Flarf & Alt-Lit (2000s–2010s)

Internet vernacular, sampling (ethical debates). Themes: irony, self-presentation. - Anthropocene/Climate Ethics Essays & Eco-Poetics (2010s–present)

Amitav Ghosh, Rebecca Solnit (essayist), Jorie Graham. Themes: nonhuman agency, scale.

The Foundation Stones: Early English Literature (450-1500)

Anglo-Saxon Literature: The Germanic Roots

The origins of English literature trace back to the Anglo-Saxon period (450-1066), when Germanic tribes established literary traditions that would profoundly influence the English language and its literature. Beowulf, the seminal epic poem of this era, exemplifies the heroic tradition with its alliterative verse patterns and exploration of honor, loyalty, and mortality. The anonymous Beowulf poet crafted a narrative that combined pagan Germanic traditions with emerging Christian influences, creating what scholars recognize as “the only complete epic poem in an ancient Germanic language”.

Religious poetry flourished under figures like Caedmon and Cynewulf, who transformed biblical themes through Anglo-Saxon poetic techniques. Caedmon’s brief nine-line hymn represents the earliest known English religious poetry, while Cynewulf’s signed works demonstrate sophisticated theological reflection within the Germanic heroic framework. These foundational texts established alliterative verse as the dominant poetic form, employing complex patterns of consonant repetition that would resurface centuries later during the Alliterative Revival.

Middle English Literature: The Transformation Period

The Norman Conquest of 1066 initiated the Middle English period (1066-1500), marked by linguistic transformation and cultural synthesis. This era witnessed the evolution from Old English to recognizably modern English, facilitated by the Great Vowel Shift and French linguistic influences. Geoffrey Chaucer emerged as the preeminent figure of this period, earning recognition as the “Father of English Literature” for his role in legitimizing English as a literary language.

The Canterbury Tales (c. 1387-1400) represents Chaucer’s masterpiece and one of the most significant works in English literature. This collection of twenty-four stories, told by pilgrims traveling to Thomas Becket’s shrine, provides an unparalleled portrait of fourteenth-century English society. Chaucer’s genius lies in his character development and social observation, creating what scholars describe as “a vast and minute portrait gallery of the social state of England in the fourteenth century”.

The Alliterative Revival (1300-1500) saw poets returning to Anglo-Saxon verse patterns, producing works like Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and Piers Plowman. This movement demonstrated the enduring power of Germanic poetic traditions while addressing contemporary social and religious concerns. William Langland’s Piers Plowman particularly exemplifies this period’s engagement with social criticism and spiritual allegory.

Renaissance Humanism and Literary Innovation (1500-1660)

The English Renaissance: Classical Revival and Humanist Ideals

The English Renaissance (1500-1660) brought transformative changes to literature through humanist philosophy, classical learning, and artistic experimentation. This period encompassed multiple sub-movements, including the Elizabethan Age (1558-1603), Jacobean Age (1603-1625), Caroline Age (1625-1649), and Commonwealth Period (1649-1660).

William Shakespeare stands as the towering figure of this era, revolutionizing drama through psychological complexity, poetic language, and universal themes. His works, from early comedies to late tragedies, demonstrate the Renaissance fascination with human nature, classical antiquity, and moral ambiguity. The Elizabethan Theatre movement created public playhouses that democratized dramatic entertainment while fostering unprecedented artistic achievement.

Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene exemplifies Renaissance allegorical poetry, combining medieval romance with Protestant theology and classical mythology. The Sonnet Sequences movement saw poets like Philip Sidney and Shakespeare perfecting both Petrarchan and Shakespearean sonnet forms, creating intimate explorations of love, beauty, and mortality.

Metaphysical and Cavalier Traditions

The Metaphysical Poetry movement (1600-1680) introduced intellectual complexity and elaborate conceits to English verse. John Donne, the movement’s founder, combined physical and spiritual elements through “unified sensibility,” creating what T.S. Eliot praised as the fusion of thought and feeling. Donne’s “Holy Sonnets” and love poems demonstrate the metaphysical technique of linking “heterogeneous ideas” through ingenious comparisons and paradoxes.

George Herbert refined metaphysical techniques for devotional purposes in “The Temple,” while Andrew Marvell applied them to both sacred and secular themes. The movement’s influence extended well beyond the seventeenth century, inspiring twentieth-century poets like Eliot and W.B. Yeats.

Contrasting with metaphysical complexity, the Cavalier Poetry movement (1625-1660) emphasized classical elegance and courtly refinement. Robert Herrick, Richard Lovelace, and Thomas Carew created lyrics celebrating beauty, love, and the carpe diem theme while maintaining sophisticated craftsmanship.

Neoclassical Order and Satirical Mastery (1660-1798)

Restoration Literature: Wit and Social Commentary

The Restoration Period (1660-1700) marked a decisive shift toward neoclassical principles of order, reason, and satirical observation. John Dryden established himself as the era’s defining voice, earning the period recognition as the “Age of Dryden”. His satirical masterpiece “Absalom and Achitophel” demonstrated the period’s mastery of the heroic couplet and political allegory.

Restoration Comedy flourished through writers like William Congreve and William Wycherley, who created sophisticated comedies of manners that satirized contemporary society while entertaining audiences with wit and sexual frankness. These playwrights established theatrical conventions that would influence comedy for centuries.

The Augustan Age: Satirical Perfection

The Augustan Age (1700-1750) achieved satirical perfection through Alexander Pope and Jonathan Swift. Pope’s “The Rape of the Lock” and “The Dunciad” exemplify the period’s mock-heroic technique, applying epic grandeur to trivial subjects for satirical effect. His “Essay on Criticism” established critical principles that governed neoclassical aesthetics.

Swift’s “Gulliver’s Travels” represents satirical prose at its most effective, using fantastical voyages to examine human nature and social institutions. The period’s emphasis on classical models, moral instruction, and formal perfection created works of enduring artistic merit while establishing English literary criticism as a discipline.

Sensibility and Pre-Romantic Stirrings

The Age of Sensibility (1750-1798) witnessed emotional responsiveness challenging pure rationalism. Thomas Gray’s “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard” exemplifies the period’s melancholic beauty and democratic sympathy, while Graveyard Poetry explored mortality and human transience with unprecedented emotional depth.

The emergence of the Gothic Literature movement (1760-1820) introduced supernatural terror and psychological exploration through works like Horace Walpole’s “The Castle of Otranto” (1764). Ann Radcliffe refined the genre through “The Mysteries of Udolpho,” creating the Female Gothic tradition that explored women’s experiences within patriarchal structures.

Romantic Revolution: Emotion and Individual Expression (1785-1830)

The Lake Poets and Romantic Innovation

The Romantic movement (1785-1830) revolutionized English literature through emotional authenticity, nature worship, and individual expression. William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s “Lyrical Ballads” (1798) marked the movement’s beginning, establishing poetry as “the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings”.

The Lake Poets transformed poetry through simple language, rural subjects, and philosophical depth. Wordsworth’s “The Prelude” explores individual consciousness development, while Coleridge’s “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” demonstrates the supernatural’s role in moral education. Their collaboration established principles that influenced subsequent poetry for generations.

Second Generation Romantics: Passionate Intensity

The Second Generation Romantics (1810-1830) intensified the movement’s revolutionary potential through Lord Byron, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and John Keats. Byron’s creation of the Byronic Hero introduced the dark, brooding protagonist who embodies rebellion against social conventions. His “Don Juan” combines satirical wit with romantic passion, influencing European literature’s development.

Shelley’s “Prometheus Unbound” articulates revolutionary idealism through mythological allegory, while his lyrical poems like “Ozymandias” demonstrate the period’s technical mastery. Keats achieved poetic perfection in odes that explore beauty, truth, and mortality with unprecedented sensuous richness.

Victorian Complexity and Social Realism (1832-1901)

Early Victorian Social Consciousness

Victorian Literature (1832-1901) encompassed unprecedented diversity while addressing industrial society’s challenges. The period’s literature reflected major social transformations: industrial revolution, democratic expansion, and scientific advancement. Charles Dickens exemplified early Victorian social consciousness through novels like “Oliver Twist” and “Hard Times,” which exposed industrial society’s dehumanizing effects while entertaining vast audiences.

The Brontë School (1847-1855) revolutionized the novel through psychological realism and passionate heroines. Charlotte Brontë’s “Jane Eyre” and Emily Brontë’s “Wuthering Heights” challenged Victorian gender conventions while creating complex female protagonists who assert individual autonomy against social constraint.

Pre-Raphaelite Aesthetics and Victorian Poetry

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (1848-1860) challenged Victorian artistic conventions through medieval revival and symbolic naturalism. Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Christina Rossetti created poetry that emphasized beauty, symbolism, and emotional intensity over moral instruction. Their movement influenced both visual arts and literature, establishing aestheticism as a significant cultural force.

Alfred Lord Tennyson dominated Victorian poetry through works that embodied the era’s conflicts and compromises. His “In Memoriam” addresses religious doubt and scientific discovery, while “Idylls of the King” attempts to revitalize Arthurian legend for contemporary audiences. Robert Browning’s dramatic monologues explored psychological complexity through historical and contemporary characters.

Late Victorian Aestheticism and Decadence

The Aestheticism movement (1880-1900) championed art for art’s sake against Victorian moral utilitarianism. Oscar Wilde’s “The Picture of Dorian Gray” epitomizes aesthetic philosophy while critiquing Victorian hypocrisy. The related Decadence movement (1890-1910) explored moral ambiguity and artistic excess through exotic themes and unconventional morality.

Thomas Hardy represented Victorian Naturalism (1870-1900), applying scientific determinism to rural life in novels like “Tess of the d’Urbervilles” and “Jude the Obscure”. His works demonstrate environmental and hereditary influences on character development, challenging Victorian optimism about human progress.

Modernist Experimentation and Innovation (1901-1945)

Early Modernist Pioneers

The Modernist movement (1914-1945) fundamentally transformed literary expression through experimental techniques and fragmented narratives. T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land” epitomizes modernist fragmentation, cultural criticism, and technical innovation, while his literary criticism established new aesthetic principles for twentieth-century poetry.

Virginia Woolf pioneered the Stream of Consciousness technique, exploring interior experience through novels like “Mrs. Dalloway” and “To the Lighthouse”. Her innovations in psychological realism and narrative structure influenced numerous subsequent writers while advancing feminist literary perspectives.

Imagism and Poetic Innovation

The Imagist movement (1910-1925) revolutionized poetry through precise imagery and compressed expression. Ezra Pound’s leadership established principles of direct treatment, economy of language, and musical rhythm that influenced modernist aesthetics broadly. H.D. refined imagist techniques for exploring mythology and personal experience.

James Joyce extended modernist experimentation through works like “Ulysses,” which employed stream of consciousness, mythological parallels, and linguistic experimentation to create unprecedented literary complexity. His influence on narrative technique continues to shape contemporary fiction.

War Poetry and Cultural Trauma

World War I Poetry (1914-1918) documented modern warfare’s unprecedented devastation through poets like Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon. Their realistic depictions of trench warfare challenged romantic notions of military glory while establishing anti-war poetry as a significant literary mode.

The Bloomsbury Group (1920-1940) created an intellectual community that fostered artistic innovation and social liberation. Members like Woolf, E.M. Forster, and Lytton Strachey challenged Victorian values through experimental literature and progressive social attitudes.

Post-War Literature and Contemporary Movements (1945-Present)

Post-War Disillusionment and Social Change

Post-War Literature (1945-1970) addressed the psychological and social aftermath of global conflict. George Orwell’s “1984” and “Animal Farm” created dystopian visions that continue to influence political discourse, while William Golding’s “Lord of the Flies” explored human nature’s darker aspects through allegorical narrative.

The Angry Young Men movement (1950-1960) expressed working-class frustration through realistic drama and fiction. John Osborne’s “Look Back in Anger” and Alan Sillitoe’s “Saturday Night and Sunday Morning” challenged middle-class complacency while giving voice to previously marginalized social groups.

Postmodernism and Genre Innovation

Postmodernism (1945-present) questioned traditional narrative assumptions through metafiction, fragmentation, and cultural criticism. Writers like John Fowles and Julian Barnes explored the nature of storytelling itself while examining historical consciousness and cultural memory.

Feminist Literature (1960-present) transformed literary expression through women’s perspectives and gender analysis. Doris Lessing, Margaret Atwood, and Angela Carter created works that examined women’s experiences while challenging patriarchal literary traditions.

Contemporary Diversity and Global Perspectives

Postcolonial Literature (1950-present) brought global perspectives to English literary traditions through writers like Salman Rushdie, V.S. Naipaul, and Jean Rhys. Their works explore colonial experience, cultural identity, and diaspora themes while enriching English literature through diverse voices and perspectives.

Black British Literature (1970-present) addresses immigrant experiences and racial identity through authors like Sam Selvon and Zadie Smith. These writers examine cultural fusion, belonging, and identity within British society while contributing distinctive voices to contemporary literature.

Climate Fiction (2000-present) emerges as a significant contemporary movement addressing environmental crisis through speculative narrative. Writers like Margaret Atwood and various eco-authors explore humanity’s relationship with the natural world while imagining alternative futures shaped by environmental change.

Genre Developments and Specialized Movements

Detective Fiction and Popular Genres

Detective Fiction (1841-present) established enduring popularity through Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories and Agatha Christie’s puzzle mysteries. This genre continues to evolve through contemporary writers who address social issues while maintaining traditional mystery elements.

Science Fiction (1800-present) originated with Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein” and developed through H.G. Wells and George Orwell into a major literary form. Contemporary science fiction addresses technological, social, and environmental concerns while exploring humanity’s future possibilities.

Fantasy Literature (1890-present) achieved artistic maturity through J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis, creating mythological worlds that address universal themes through imaginative narrative. This genre continues to attract readers while gaining critical recognition for literary merit.

Performance and Visual Poetry

Concrete Poetry (1950-present) transforms poetry into visual art through typographical arrangement and spatial meaning. Ian Hamilton Finlay pioneered British concrete poetry, creating works that combine linguistic and visual elements for enhanced meaning.

Performance Poetry (1960-present) revitalizes oral traditions through live presentation and audience interaction. This movement includes Spoken Word artists who combine poetry with theatrical performance, reaching diverse audiences through accessible presentation styles.

Regional and Cultural Movements

Celtic Revival and Regional Identity

The Celtic Revival (1870-1920) promoted Irish cultural nationalism through writers like W.B. Yeats and J.M. Synge. This movement influenced Irish literary renaissance while contributing to broader discussions of national identity and cultural authenticity.

Scottish Literature developed distinctive movements including Tartan Noir (1990-present), which creates crime fiction with specifically Scottish settings and themes. Writers like Ian Rankin establish regional identity while contributing to international crime fiction traditions.

Regional Poetry movements like the Liverpool Poets (1960-1980) democratized poetry through performance and accessible language. Roger McGough, Brian Patten, and Adrian Henri reached broad audiences while maintaining artistic integrity.

Digital Age and Contemporary Innovations

Technology and Literary Expression

Digital Literature (2000-present) explores new media possibilities through hypertext, multimedia elements, and online publication. This movement challenges traditional book formats while creating new possibilities for reader interaction and narrative structure.

Autofiction (2000-present) blurs boundaries between autobiography and fiction, reflecting contemporary interest in personal narrative and authentic experience. This movement addresses postmodern questions about truth and representation while maintaining literary artistry.

Environmental and Social Consciousness

Eco-Literature (1970-present) addresses humanity’s relationship with the natural world through both fiction and non-fiction. Writers like Robert Macfarlane combine scientific knowledge with literary expression to explore environmental themes and promote ecological consciousness.

Climate Fiction (2000-present) or Cli-Fi specifically addresses climate change through speculative narrative, imagining future scenarios while examining present environmental challenges. This emerging movement demonstrates literature’s continued relevance to contemporary global concerns.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What defines a literary movement in English literature?

A: A literary movement represents a group of writers sharing common aesthetic principles, thematic concerns, or stylistic innovations during a specific historical period. These movements reflect broader cultural, social, and intellectual developments while influencing subsequent literary traditions.

Q: Which literary movement had the greatest impact on English literature?

A: While impact is subjective, the Renaissance (1500-1660) and Romanticism (1785-1830) arguably transformed English literature most profoundly. The Renaissance established many foundational genres and techniques, while Romanticism revolutionized concepts of individual expression and emotional authenticity that continue to influence contemporary writing.

Q: How do contemporary movements compare to historical ones?

A: Contemporary movements like Postmodernism and Digital Literature demonstrate similar innovation and cultural responsiveness as historical movements. However, modern movements often develop more rapidly due to improved communication and global connectivity, while addressing distinctly contemporary concerns like environmental crisis and technological change.

Q: What role do social and political factors play in literary movements?

A: Social and political factors significantly influence literary movements by providing contexts, themes, and motivations for artistic expression. Major historical events like wars, social reforms, and technological advances consistently generate new literary approaches and thematic concerns.

Q: Are literary movements still relevant in the digital age?

A: Yes, literary movements remain relevant as writers continue to form communities around shared aesthetic and thematic concerns. Digital technology facilitates new forms of literary expression and community formation while traditional movement patterns persist in contemporary literary culture.

Q: How do British and American literary movements differ?

A: While sharing linguistic heritage, British and American literary movements often reflect different cultural priorities and historical experiences. British movements typically emphasize tradition, class consciousness, and imperial history, while American movements often stress individualism, democratic ideals, and frontier experiences.

Q: What distinguishes major movements from minor ones?

A: Major movements typically demonstrate significant influence on subsequent literature, broad cultural impact, and enduring relevance. They often produce multiple significant authors and works while establishing aesthetic principles that influence later writers and cultural discourse.

Q: How do literary movements influence each other?

A: Literary movements frequently react against, build upon, or synthesize elements from previous movements. Romanticism reacted against Neoclassicism, Modernism challenged Victorian conventions, and Postmodernism questioned Modernist assumptions, demonstrating literature’s ongoing evolutionary development.

Q: What current trends might become future literary movements?

A: Emerging trends like Climate Fiction, Autofiction, Digital Literature, and Anthropocene Literature may develop into significant future movements. These reflect contemporary concerns with environmental crisis, authentic experience, technological change, and humanity’s geological impact, suggesting literature’s continued responsiveness to cultural development.