100 Most Important Literary Terms Every Student Should Know

A Comprehensive Guide to Literary Analysis

In the vast landscape of literary studies, understanding the fundamental terminology is not just an academic requirement—it’s the key to unlocking the deeper meanings and artistic brilliance of literary works. As William Carlos Williams once described poetry, literature can be thought of as “a machine made of words,” and literary terms are the tools that help us understand how this intricate machinery operates1. Whether you’re analyzing Shakespeare’s complex metaphors or decoding contemporary narrative techniques, mastering these essential literary terms will transform your approach to reading, writing, and critical analysis.

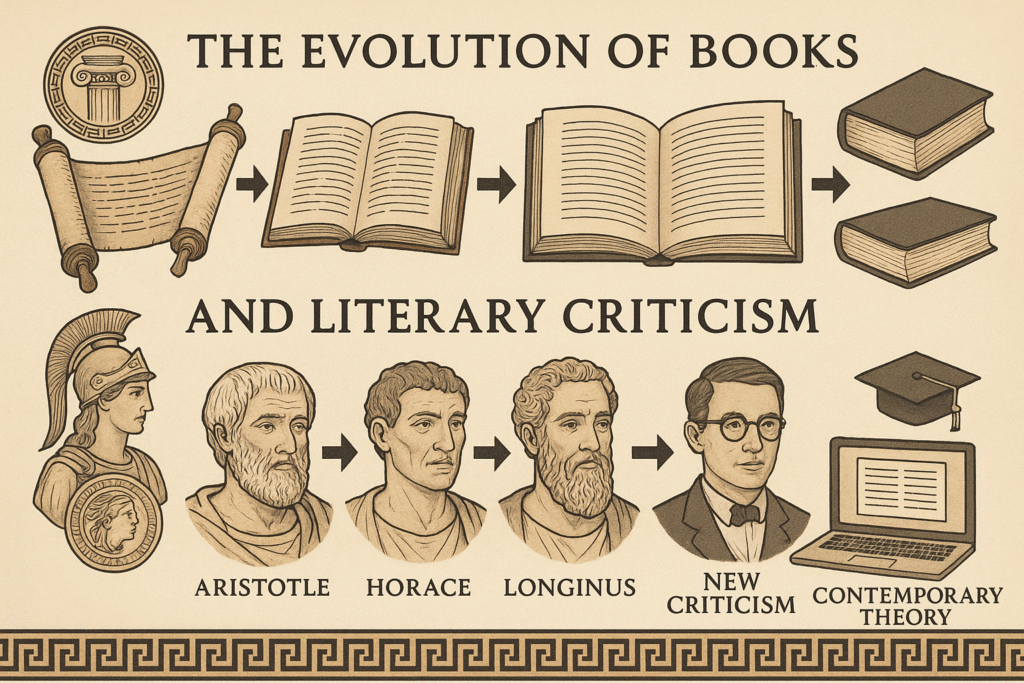

The study of literary terms traces its origins back to ancient Greece, where philosophers like Aristotle laid the foundation for literary criticism in his seminal work Poetics. Today, these concepts continue to evolve, adapting to new forms of expression while maintaining their classical roots23. For students of English literature, educators, and enthusiasts alike, this comprehensive guide presents 100 essential literary terms that form the backbone of literary analysis.

Historical Development of Literary Terminology

Ancient Foundations

The systematic study of literary devices began with Aristotle’s Poetics (c. 335 BCE), which introduced fundamental concepts such as mimesis (imitation) and catharsis (emotional purging). Aristotle’s analytical approach to drama and poetry established many terms we still use today, including anagnorisis (recognition) and hamartia (tragic flaw). His work complemented Plato’s earlier critiques in *Thed influence scholars for millennia.

The Romans further developed these concepts through the works of Horace, whose Ars Poetica emphasized the dual purpose of literature: to instruct and delight. Horace’s influence extended well into the Renaissance, where critics like Sir Philip Sidney argued in his Defence of Poesie (1595) that poetry’s imaginative power surpassed both philosophy and history.

Renaissance and Neoclassical Refinement

The Renaissance period marked a crucial turning point in literary terminology development. Giorgio Valla’s translation of Aristotle’s Poetics into Latin in 1498 made classical concepts accessible to a broader scholarly audience3. Critics like Lodovico Castelvetro codified dramatic principles, extending Aristotle’s concept of the three unities (time, place, and action) that would dominate theatrical criticism for centuries.

During this period, the Pléiade movement in France, led by Pierre de Ronsard and Joachim du Bellay, emphasized the importance of classical imitation while advocating for vernacular literature3. Their work established many terms related to prosody and poetic form that remain central to literary analysis today.

Modern Evolution and Critical Theory

The 20th century witnessed an explosion of literary terminology through various critical movements. New Criticism, championed by scholars like T.S. Eliot and Cleanth Brooks, introduced the concept of close reading and emphasized analyzing texts independently of authorial intent and historical context. This movement coined terms like objective correlative and refined concepts of ambiguity and paradox.

Structuralism, building on Ferdinand de Saussure’s linguistic theories, contributed terms like signifier and signified, fundamentally changing how we understand literary meaning. Subsequently, poststructuralism and deconstruction introduced concepts of intertextuality and différance, challenging traditional notions of fixed meaning in texts.

Essential Categories of Literary Terms

Understanding literary terms becomes more manageable when organized into coherent categories. Each category serves specific analytical purposes and often overlaps with others, creating the rich tapestry of literary analysis.

Foundational Elements

These terms form the basic building blocks of literary analysis, essential for understanding any text’s fundamental components. They include concepts like theme, setting, character, and plot—elements that appear in virtually every form of narrative literature.

Figurative Language and Rhetoric

Perhaps the most recognizable category, these terms deal with non-literal language use. Metaphors, similes, personification, and irony fall into this category, serving as the primary tools authors use to create vivid imagery and convey complex emotions.

Narrative and Structural Elements

These terms focus on how stories are constructed and told. Point of view, foreshadowing, climax, and denouement help us understand the mechanics of storytelling and how authors manipulate reader expectations.

Sound and Rhythm

Particularly important in poetry, these terms describe the musical qualities of language. Alliteration, assonance, meter, and rhyme scheme help create the sonic landscape of literary works.

The Core 100 Literary Terms

Foundational Terms (1-25)

1. Theme – The central idea or underlying meaning of a literary work. Unlike a simple topic, theme represents the author’s commentary on the human condition. In Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, themes include racial injustice and moral courage.

2. Setting – The time, place, and social environment in which a story takes place. Gothic literature, such as Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights, uses setting as almost an additional character, with cold, miserable buildings reflecting the inhabitants’ emotional states.

3. Character – Any person, animal, or personified object in a literary work. Characters can be round (complex, multi-dimensional) or flat (simple, one-dimensional), dynamic (changing) or static (unchanging).

4. Characterization – The methods an author uses to develop characters, including direct description, dialogue, actions, and other characters’ reactions.

5. Plot – The sequence of events in a story, typically following the structure of exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution.

6. Conflict – The struggle between opposing forces that drives the plot. Types include man vs. man, man vs. nature, man vs. society, and man vs. self.

7. Symbolism – The use of objects, colors, figures, or other elements to represent ideas or concepts beyond their literal meaning. The green light in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby symbolizes hope and the American Dream.

8. Imagery – Vivid descriptive language that appeals to the senses. Edgar Allan Poe masterfully uses visual and auditory imagery in “The Raven”: “And the silken, sad, uncertain rustling of each purple curtain”.

9. Tone – The author’s attitude toward the subject matter or audience, conveyed through word choice and style.

10. Mood – The emotional atmosphere that the author creates for the reader, distinct from tone in that it describes the reader’s emotional response.

11. Diction – The author’s choice of words and phrases, which can be formal, informal, colloquial, or slang.

12. Point of View – The perspective from which a story is told: first person (I), second person (you), third person limited, or third person omniscient.

13. Narrator – The voice telling the story, which may or may not be the author. Reliable and unreliable narrators provide different levels of trustworthiness.

14. Protagonist – The main character in a literary work, often facing the central conflict.

15. Antagonist – The character or force that opposes the protagonist.

16. Foreshadowing – Hints or clues about future events in the story. Shakespeare uses foreshadowing in Romeo and Juliet when Romeo says, “My life were better ended by their hate, than death prorogued, wanting of thy love”.

17. Flashback – An interruption in the chronological sequence to present earlier events.

18. Climax – The turning point or highest point of tension in a story.

19. Resolution/Denouement – The conclusion where conflicts are resolved and loose ends are tied up.

20. Irony – A contrast between expectation and reality, existing in three main types: verbal, situational, and dramatic.

21. Allusion – An indirect reference to another work of literature, person, place, or event.

22. Metaphor – A direct comparison between two unlike things without using “like” or “as.” Shakespeare writes, “All the world’s a stage”.

23. Simile – A comparison using “like,” “as,” or “than.” Robert Burns’s “My love is like a red, red rose” exemplifies this device.

24. Personification – Giving human characteristics to non-human things. Emily Dickinson personifies death in “Because I could not stop for Death”.

25. Hyperbole – Deliberate exaggeration for emphasis or dramatic effect.

Figurative Language and Rhetoric (26-50)

26. Alliteration – The repetition of initial consonant sounds in nearby words. Shakespeare uses this device in Romeo and Juliet: “From forth the fatal loins of these two foes”.

27. Onomatopoeia – Words that imitate the sounds they represent, such as “buzz,” “crash,” or “whisper”.

28. Synecdoche – A figure of speech where a part represents the whole or vice versa. “All hands on deck” uses hands to represent sailors.

29. Metonymy – Substituting the name of something with something closely associated with it. “The White House announced” uses the building to represent the presidency.

30. Oxymoron – A combination of contradictory terms, such as “deafening silence” or “bitter sweet”.

31. Paradox – A seemingly contradictory statement that reveals a deeper truth. John Donne’s “Death, be not proud” explores the paradox that death is not final.

32. Satire – The use of humor, irony, or exaggeration to criticize and expose flaws in human behavior or society.

33. Apostrophe – Directly addressing someone or something not present, such as abstract concepts or deceased persons.

34. Rhetoric – The art of persuasive speaking or writing, encompassing various techniques to influence audiences.

35. Euphemism – A mild or indirect term substituted for one considered too harsh or direct.

36. Antithesis – The juxtaposition of contrasting ideas in balanced phrases or clauses. Shakespeare’s “Fair is foul, and foul is fair” from Macbeth exemplifies this device.

37. Chiasmus – A reversal of grammatical structures in successive phrases or clauses.

38. Anaphora – The repetition of words or phrases at the beginning of successive clauses. Shakespeare uses this in Romeo and Juliet: “It is too rash, too unadvised, too sudden”.

39. Epistrophe – The repetition of words or phrases at the end of successive clauses.

40. Allusion – A reference to another work of literature, historical event, or cultural element.

41. Allegory – A narrative where characters and events represent abstract ideas or principles. George Orwell’s Animal Farm is an allegory for the Russian Revolution.

42. Symbolism – The use of symbols to represent ideas or concepts beyond their literal meaning.

43. Motif – A recurring element that has symbolic significance in a story.

44. Archetype – Universal symbols, characters, or themes that recur across cultures and literature.

45. Conceit – An elaborate or extended metaphor, particularly common in metaphysical poetry.

46. Litotes – A form of understatement that affirms by denying the opposite.

47. Zeugma – A figure of speech where a word applies to multiple parts of a sentence.

48. Synesthesia – The description of one sensory experience in terms of another.

49. Juxtaposition – Placing two elements side by side to highlight their differences or similarities.

50. Contrast – The arrangement of opposite elements to create effect and meaning.

Narrative and Structural Elements (51-75)

51. Stream of Consciousness – A narrative technique that presents a character’s continuous flow of thoughts and feelings.

52. In Medias Res – Beginning a story in the middle of action rather than at the chronological beginning.

53. Frame Narrative – A story within a story, where one narrative serves as the frame for another.

54. Epistolary – A narrative told through documents such as letters, diary entries, or emails.

55. Unreliable Narrator – A narrator whose credibility is compromised, forcing readers to question the truth of the narrative.

56. Omniscient Narrator – A narrator who knows the thoughts and feelings of all characters.

57. Limited Third Person – A narrative perspective restricted to one character’s point of view.

58. Interior Monologue – The presentation of a character’s inner thoughts and feelings.

59. Dialogue – Conversation between characters that advances plot and reveals character.

60. Monologue – An extended speech by one character.

61. Soliloquy – A speech in which a character, usually alone, expresses thoughts aloud.

62. Aside – A remark made by a character that other characters on stage cannot hear.

63. Dramatic Irony – When the audience knows something that characters do not.

64. Situational Irony – When the outcome differs significantly from expectations.

65. Verbal Irony – When a speaker says one thing but means another.

66. Red Herring – A misleading clue designed to distract from the real solution.

67. Cliffhanger – An ending that leaves the audience in suspense.

68. Epiphany – A sudden moment of insight or realization for a character.

69. Catharsis – The emotional release experienced by the audience, particularly in tragedy.

70. Hamartia – The tragic flaw that leads to a hero’s downfall.

71. Hubris – Excessive pride that leads to a character’s downfall.

72. Peripeteia – A sudden reversal of fortune in a dramatic work.

73. Anagnorisis – The moment of recognition or discovery in a tragedy.

74. Deus Ex Machina – An unexpected intervention that resolves the plot.

75. MacGuffin – An object or element that drives the plot but is ultimately unimportant.

Advanced and Contemporary Terms (76-100)

76. Metafiction – Fiction that self-consciously addresses the devices of fiction40.

77. Intertextuality – The relationship between texts through references, allusions, or structural similarities37.

78. Pastiche – A work that imitates the style of another work or period40.

79. Parody – A humorous imitation that exaggerates characteristics of the original41.

80. Magical Realism – A narrative style that combines realistic and fantastical elements42.

81. Modernism – A literary movement emphasizing experimentation with form and technique42.

82. Postmodernism – A movement that questions traditional narrative structures and absolute meaning40.

83. Bildungsroman – A coming-of-age novel that follows a character’s psychological development15.

84. Picaresque – A narrative following a roguish protagonist through episodic adventures15.

85. Gothic – A literary mode characterized by mystery, supernatural elements, and dark atmosphere18.

86. Romanticism – A movement emphasizing emotion, individualism, and nature4.

87. Realism – A movement focused on depicting everyday life accurately42.

88. Naturalism – An extension of realism that emphasizes deterministic forces42.

89. Symbolism – A movement using symbols to represent ideas and emotions42.

90. Impressionism – A style focusing on subjective perception rather than objective reality42.

91. Expressionism – A movement emphasizing emotional experience over physical reality42.

92. Surrealism – A movement exploring the unconscious mind and dream-like imagery42.

93. Minimalism – A style characterized by spare, precise language and understated emotion42.

94. Maximalism – A style characterized by elaborate language and complex narratives42.

95. Postcolonialism – Literature that examines the effects of colonialism and cultural identity42.

96. Feminism – Literary criticism examining gender roles and women’s experiences4.

97. Ecocriticism – Literary criticism examining the relationship between literature and environment42.

98. New Historicism – An approach that examines literature within its historical context4.

99. Deconstruction – A critical approach that questions the stability of meaning in texts4.

100. Reader-Response Theory – A critical approach focusing on the reader’s role in creating meaning4.

Literary Terms in Practice: Classical and Modern Examples

Shakespeare’s Mastery of Literary Devices

William Shakespeare’s works serve as a masterclass in literary device usage. His employment of iambic pentameter creates the rhythmic foundation for much of his dramatic verse, while his innovative use of metaphysical conceits pushes the boundaries of Elizabethan poetry.

In Hamlet, Shakespeare demonstrates dramatic irony when the audience knows Claudius murdered Hamlet’s father, but most characters remain unaware. The famous soliloquy “To be, or not to be” showcases antithesis and metaphor while revealing Hamlet’s internal conflict through stream of consciousness29.

Anaphora appears throughout Shakespeare’s works, as Juliet’s passionate declaration: “It is too rash, too unadvised, too sudden; Too like the lightning, which doth cease to be”. This repetition emphasizes her concerns about their hasty romance while creating musical rhythm.

Edgar Allan Poe’s Gothic Techniques

Edgar Allan Poe’s distinctive style demonstrates how literary devices create atmosphere and psychological intensity. His diction employs archaic and elevated vocabulary to create formal, Gothic tone. In “The Tell-Tale Heart,” Poe uses first-person narration to blur the lines between reality and madness, creating an unreliable narrator whose credibility deteriorates throughout the story.

Poe’s sentence structure features complex punctuation—commas, semicolons, and dashes—that builds suspense and reflects his characters’ psychological states. His frequent use of hyphens indicates mental agitation: “It is impossible to say how first the idea entered my brain; but once conceived, it haunted me day and night”.

The author’s mastery of symbolism appears in works like “The Masque of the Red Death,” where the ebony clock represents mortality’s inevitability. His imagery consistently appeals to multiple senses, creating immersive, often terrifying experiences for readers.

Jane Austen’s Ironic Voice

Jane Austen’s novels demonstrate sophisticated use of irony and social satire. The opening sentence of Pride and Prejudice—”It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife”—exemplifies verbal irony. The statement appears to describe wealthy men’s desires but actually reveals society’s expectations for women to secure advantageous marriages.

Austen employs free indirect discourse to blend narrative voice with character consciousness, allowing subtle commentary on social conventions. Her characterization through dialogue reveals personality traits and social pretensions, as seen in Mr. Collins’s obsequious speeches or Lady Catherine’s imperious declarations.

Situational irony pervades Austen’s plotting: proud Darcy falls for Elizabeth, whom he initially scorns, while Elizabeth’s prejudice against Darcy blinds her to Wickham’s true character. These ironies illuminate themes about judgment, first impressions, and social mobility.

The Evolution of Literary Criticism

From Formalism to Digital Humanities

The development of literary terminology reflects broader changes in critical theory and methodology. New Criticism emphasized close reading and textual analysis, contributing terms like organic unity and aesthetic object4. This movement treated literary works as self-contained artifacts whose meaning emerged from internal relationships between elements.

Structuralism introduced linguistic concepts to literary analysis, emphasizing binary oppositions and narrative structures. Critics like Claude Lévi-Strauss and Roland Barthes contributed terms like cultural code and death of the author, fundamentally changing how scholars approach textual meaning4.

Poststructuralism and deconstruction, associated with Jacques Derrida and Michel Foucault, questioned stable meaning and introduced concepts like différance and discourse. These movements emphasized intertextuality and the impossibility of final interpretive authority4.

Contemporary Critical Approaches

Modern literary criticism embraces diverse perspectives that have expanded terminology significantly. Feminist criticism contributed terms like écriture féminine and gynocriticism, while postcolonial theory introduced concepts like subaltern and cultural hybridity4.

Digital humanities has created new analytical possibilities, introducing terms like distant reading, text mining, and computational analysis. These approaches allow scholars to examine large corpora of texts, revealing patterns invisible to traditional close reading4.

Ecocriticism examines literature’s relationship with environmental concerns, contributing terms like nature writing and environmental justice. This emerging field reflects growing awareness of climate change and humanity’s relationship with the natural world42.

Mastering Literary Analysis Through Practice

Understanding literary terms requires active application rather than passive memorization. Successful literary analysis combines close reading with broader cultural and historical knowledge47. Students should practice identifying devices in various texts, from classical works to contemporary literature.

Pattern recognition helps identify recurring devices within works and across authors. Shakespeare’s consistent use of flower imagery in Hamlet creates symbolic networks that reinforce themes about beauty’s fragility and corruption’s spread48. Similarly, Poe’s color symbolism—particularly his use of red and black—creates atmospheric consistency across multiple stories49.

Effective analysis connects literary devices to larger interpretive questions. Rather than simply identifying metaphors or symbols, skilled readers examine how these devices contribute to theme development, character revelation, or social commentary. The goal is not cataloging techniques but understanding their cumulative effect on meaning and reader experience.

Contemporary literature continues evolving these traditional concepts. Authors like Toni Morrison, Gabriel García Márquez, and Haruki Murakami blend classical techniques with innovative approaches, creating works that challenge conventional boundaries42. Understanding both traditional and emerging terminology prepares students for literature’s continued evolution.

Literary analysis ultimately serves the broader goal of cultural literacy—understanding how texts reflect and shape human experience across time and cultures. Mastering literary terminology provides tools for engaging with this rich tradition while developing critical thinking skills applicable far beyond English classrooms.

These 100 literary terms represent essential vocabulary for serious literary study. However, terminology alone cannot substitute for careful reading, thoughtful analysis, and cultural awareness. The most successful students combine technical knowledge with genuine curiosity about human experience as expressed through literature’s infinite varieties.

As T.S. Eliot wrote in Four Quartets, “For last year’s words belong to last year’s language / And next year’s words await another voice”50. Literary terminology continues evolving as new voices join the conversation, ensuring that tomorrow’s students will encounter both familiar concepts and innovative approaches to understanding literature’s enduring power.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. What’s the difference between a metaphor and a simile?

A simile makes an explicit comparison using words like “like,” “as,” or “than” (e.g., “Her voice was like music”), while a metaphor makes an implicit comparison by stating that one thing is another (e.g., “Her voice was music”). Metaphors tend to create more vivid and immediate impact because they’re more obviously non-literal, whereas similes maintain some distance through their comparative structure.

2. How can I identify literary devices while reading?

Start by creating a mental checklist of common devices like imagery, symbolism, metaphor, and irony52. Look for patterns in language—repeated sounds might indicate alliteration or assonance, while recurring objects or concepts might be symbols or motifs. Pay attention to unusual word choices, as these often signal figurative language or specific diction choices47. Practice with familiar texts first, then apply these skills to new readings.

3. Why do authors use literary devices instead of writing plainly?

Literary devices serve multiple purposes: they create emphasis, enhance imagery, establish mood and tone, and add layers of meaning that engage readers more deeply613. They help authors express complex emotions and ideas that might be difficult to convey through straightforward prose. Additionally, devices like metaphor and symbolism allow writers to connect abstract concepts to concrete experiences, making their work more relatable and memorable.

4. What’s the difference between theme and motif?

Theme is the central idea or message of a literary work—the author’s commentary on life, society, or human nature13. Motif is a recurring element (image, sound, action, or idea) that supports or develops the theme25. For example, in Shakespeare’s Macbeth, the theme might be the corrupting nature of unchecked ambition, while motifs include sleep, blood, and crown imagery that reinforce this theme throughout the play.

5. How do I know if a narrator is reliable or unreliable?

An unreliable narrator shows signs of bias, mental instability, limited knowledge, or deliberate deception35. Look for contradictions in their account, obvious gaps in logic, admissions of memory problems, or other characters’ reactions that contradict the narrator’s version of events. Edgar Allan Poe’s narrators often demonstrate unreliability through their defensive protestations of sanity or their obsessive behavior patterns.

6. What’s the difference between mood and tone?

Tone reflects the author’s attitude toward the subject matter, conveyed through word choice and style19. Mood is the emotional atmosphere the author creates for the reader—how the text makes you feel. For example, an author might use a sarcastic tone when discussing social inequality, which creates an angry or frustrated mood in readers. Tone is the author’s voice; mood is the reader’s emotional response.

7. Why is understanding literary terms important for students?

Literary terminology provides the vocabulary needed for precise literary analysis and critical thinking53. These terms help students articulate their interpretations clearly, engage in meaningful discussions about literature, and write more sophisticated analytical essays. Understanding these concepts also enhances reading comprehension and appreciation of literary artistry, skills that transfer to other disciplines and professional contexts.

8. How do literary terms apply to contemporary and non-Western literature?

While many literary terms originated from Western classical traditions, they apply broadly across cultures and time periods. Contemporary authors use both traditional devices and innovative techniques, often blending multiple cultural traditions. For example, magical realism emerged from Latin American writers but now appears globally. Non-Western literatures have their own rich traditions of figurative language and narrative techniques that complement and expand traditional terminology.

9. Should I memorize all these terms, or is understanding more important?

Understanding and application matter more than rote memorization. Focus on mastering key concepts like metaphor, symbolism, irony, character, setting, and theme first, then gradually expand your vocabulary. The goal is developing analytical skills rather than creating a mental dictionary. Regular reading and practice applying these terms will help you internalize them naturally while building genuine literary expertise.

About www.EnglishLiterature.in: We are dedicated to providing comprehensive, accessible guidance for students, educators, and literature enthusiasts. Our expert team combines academic rigor with practical application to help readers develop deeper appreciation for literary artistry and critical analysis skills.

Exploring Resistance: How Marginalized Voices Challenge the Canon