100 Most Powerful Symbols in English Literature

Literary symbolism has shaped the landscape of English literature for centuries, providing authors with a rich tapestry of meaning that transcends the literal word. From Shakespeare’s tempests to Dickens’ fog, from Hawthorne’s scarlet letter to Morrison’s beloved, symbols serve as the invisible threads that weave deeper significance into narrative fabric. This comprehensive exploration examines the one hundred most powerful symbols that have defined, enriched, and elevated English literature throughout its evolution.

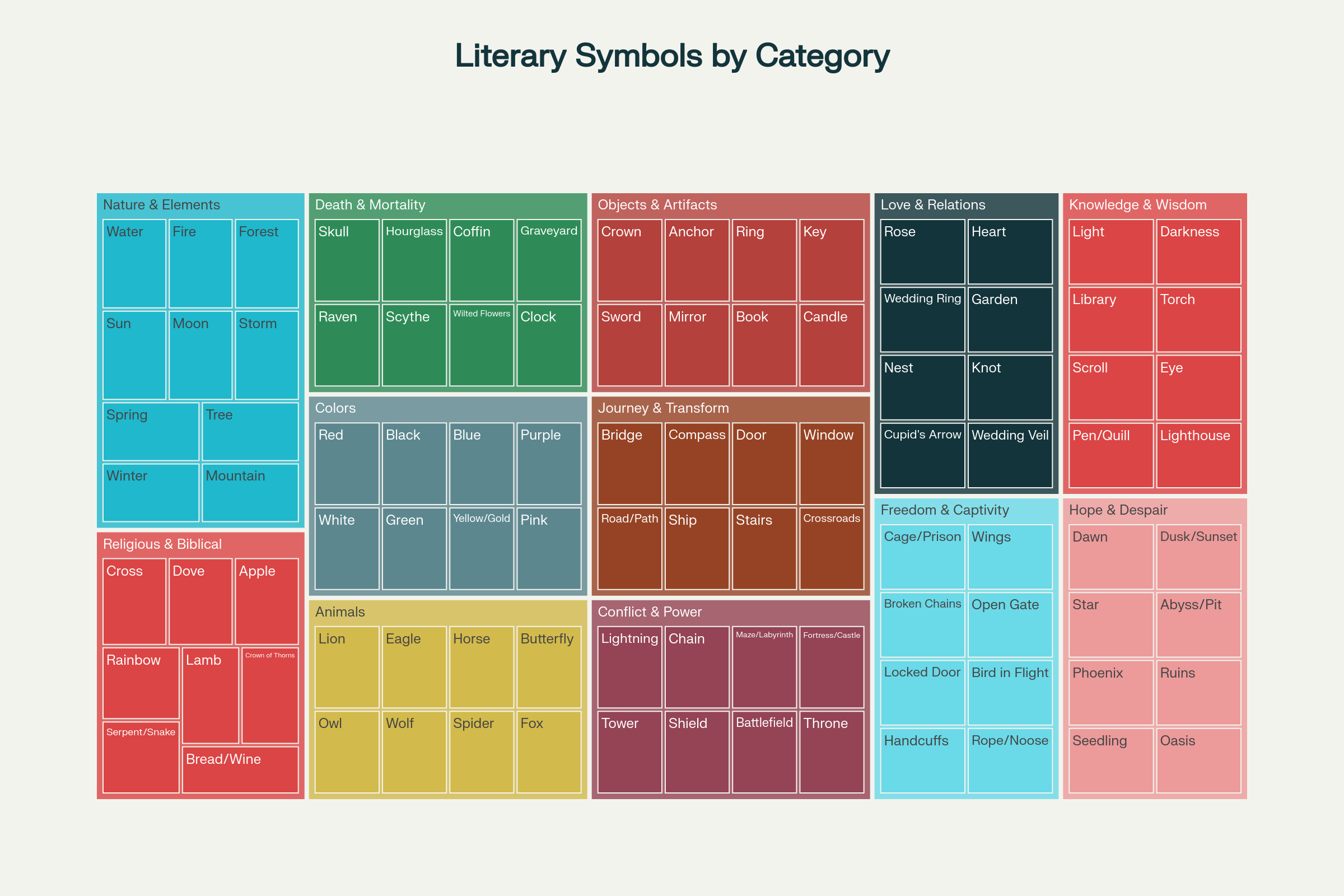

The 100 Most Powerful Symbols in English Literature – A comprehensive categorization of literary symbols and their meanings

The Foundation of Literary Symbolism

Symbolism represents one of literature’s most sophisticated and enduring techniques, allowing writers to communicate complex ideas through concrete imagery. Unlike mere metaphors or similes that draw direct comparisons, literary symbols operate on multiple levels simultaneously, creating layers of meaning that invite readers to engage in active interpretation. The power of these symbols lies not only in their immediate recognition but in their ability to evoke universal human experiences while maintaining cultural specificity.

Origins and Evolution

The tradition of symbolic representation in English literature draws from diverse sources: biblical narratives, classical mythology, folklore traditions, and natural phenomena. These symbols have evolved through centuries of literary usage, gaining complexity and nuance as successive generations of writers have employed them in new contexts. What began as relatively straightforward religious or mythological references has transformed into a sophisticated symbolic language that can convey the most subtle psychological and philosophical concepts.

Religious and Biblical Symbolism

The influence of Christian symbolism on English literature cannot be overstated. The Bible has provided a foundational symbolic vocabulary that permeates literary works from medieval mystery plays to contemporary fiction11. The cross stands as perhaps the most recognizable symbol, representing not merely Christianity but concepts of sacrifice, redemption, and the intersection of divine and human realms. The dove, consistently symbolizing peace and the Holy Spirit, appears across genres and centuries as a messenger of hope and divine intervention.

The apple carries the weight of humanity’s fall from grace, symbolizing both knowledge and temptation. This duality makes it particularly powerful in literary contexts where characters face moral choices. The serpent operates as its counterpart, embodying deception, evil, and the corruption of innocence. These symbols work together to create what literary scholars term a “symbolic constellation”—interrelated images that reinforce thematic content.

Biblical narratives have also contributed symbols of covenant and promise. The rainbow appears in literature as a sign of hope after devastation, drawing directly from the Noah narrative while expanding to encompass broader themes of renewal and divine mercy. The lamb represents innocence and sacrifice, particularly powerful in works dealing with themes of martyrdom or the loss of innocence.

Nature and Elemental Symbolism

Natural elements provide literature’s most primal and universal symbols. Water serves multiple symbolic functions: purification, rebirth, life force, and change. From baptismal imagery to the crossing of rivers as life transitions, water symbolism operates on both conscious and unconscious levels. In works like The Odyssey and The Old Man and the Sea, water represents the vast unknown and humanity’s struggle against forces beyond control.

Fire embodies transformation, passion, and divine power. It can represent both creative and destructive forces—the hearth fire of home and comfort contrasted with the consuming flames of hell or passion. Forest symbolism taps into humanity’s deepest psychological fears and desires, representing the unconscious mind, the unknown, and the place where transformation occurs. From Dante’s dark wood to the forests of Shakespeare’s comedies, these natural spaces serve as testing grounds for character development.

The sun and moon create a symbolic binary that has influenced literature across cultures. The sun typically represents masculine energy, consciousness, divine power, and enlightenment, while the moon embodies feminine mystery, cycles, romance, and the subconscious. Seasonal symbolism provides a natural framework for exploring themes of birth, growth, decay, and renewal, with spring representing hope and new beginnings, summer suggesting fullness and maturity, autumn indicating decline and harvest, and winter symbolizing death and dormancy.

Death and Mortality Symbols

Literature’s preoccupation with mortality has generated a rich symbolic vocabulary surrounding death. The skull serves as the ultimate memento mori, reminding readers of life’s brevity and the inevitability of death. From Hamlet’s contemplation of Yorick’s skull to medieval danse macabre imagery, the skull transcends cultural boundaries to speak to universal human fears.

The raven gained particular prominence through Edgar Allan Poe’s masterpiece, becoming synonymous with death, doom, and mysterious prophecy. This bird’s black plumage and association with carrion made it a natural symbol for mortality and the supernatural. The hourglass represents time’s passage and mortality’s approach, while the scythe evokes both harvest and the Grim Reaper’s tool.

Clock imagery serves to emphasize urgency and the relentless march of time toward death. Wilted flowers symbolize the transience of beauty and life, particularly powerful in contexts dealing with lost youth or unfulfilled potential. These symbols work together to create what scholars call “thanatological imagery”—a symbolic system that helps literature grapple with humanity’s greatest mystery.

Color Symbolism

Colors in literature carry profound symbolic weight, often operating below the threshold of conscious awareness. Red commands attention as the color of blood, passion, anger, and life force. In The Scarlet Letter, red embodies both sin and vitality, while in many works it signals danger or intense emotion. The complexity of red symbolism allows authors to layer multiple meanings within single images.

White presents fascinating contradictions, symbolizing purity and innocence in Western traditions while representing death and mourning in others. This duality makes white particularly effective in literature dealing with themes of moral ambiguity. Black consistently represents death, evil, mystery, and the unknown across cultures and literary periods.

Green carries associations with nature, growth, envy, and hope. In The Great Gatsby, the green light becomes a complex symbol of desire, hope, and the corrupting influence of the American Dream. Blue evokes melancholy, spirituality, and depth, while purple suggests royalty, mystery, and transformation. Yellow and gold can represent divine light and wealth, but also decay and cowardice, demonstrating how symbolic meaning depends heavily on context.

Animal Symbolism

Animals in literature serve as powerful symbols because they embody recognizable traits while remaining distinct from human characters. The lion represents courage, strength, and nobility, drawing from both biblical tradition and natural observation. The owl symbolizes wisdom and mystery, its nocturnal nature associating it with hidden knowledge and sometimes death.

The eagle soars as a symbol of freedom, power, and divine connection, while the wolf embodies wildness, danger, and pack loyalty. The horse represents nobility, freedom, and the journey, serving as humanity’s companion in exploration and conquest. The butterfly provides one of nature’s most perfect symbols of transformation, representing the soul’s metamorphosis and the possibility of resurrection.

The spider weaves webs of fate and creativity, often associated with feminine power and the interconnectedness of existence. The fox embodies cunning and intelligence, frequently appearing as a trickster figure who challenges established order. These animal symbols work because they combine observable characteristics with cultural associations built over centuries of literary usage.

Objects and Artifacts

Human-made objects gain symbolic power through their cultural significance and literary usage. The crown represents authority and power, but also the burden of leadership and isolation that comes with rule. The sword embodies justice, honor, and conflict, serving as both protector and destroyer. The anchor provides stability and hope, particularly powerful in maritime literature and works dealing with themes of security.

The mirror reflects truth, self-knowledge, and vanity, creating opportunities for character revelation and symbolic doubling. The ring symbolizes commitment, eternity, and binding power, from wedding ceremonies to Tolkien’s exploration of corruption. The key unlocks mysteries, opportunities, and hidden knowledge, often serving as a symbol of enlightenment or access to forbidden realms.

Books represent knowledge, wisdom, and the power of literacy to transform lives. Candles embody hope, spirituality, and the fragile nature of life, their flames serving as metaphors for consciousness and divine presence. These objects gain power through their integration into narrative structure and thematic development.

Journey and Transformation Symbols

The journey motif represents one of literature’s most fundamental symbolic patterns. The bridge symbolizes transition, connection, and the crossing from one state of being to another. Roads and paths represent life’s journey, choices, and destiny, from Frost’s diverging roads to the yellow brick road of Oz.

The compass provides direction and guidance, symbolizing purpose and navigation through life’s complexities. Ships carry characters on literal and metaphorical journeys, representing exploration, adventure, and life’s passage. Doors offer opportunity and transition, while windows provide perspective and insight into other worlds.

Stairs symbolize ascension, progress, and spiritual development, while crossroads represent crucial decisions and life-changing moments. These symbols work together to create what scholars term “liminal imagery”—representations of threshold states and transitional moments that define character development.

Conflict and Power Symbols

Literature’s exploration of power dynamics has generated symbols that represent authority, struggle, and resistance. Lightning embodies divine power, sudden revelation, and dramatic change. The tower represents isolation, pride, and spiritual aspiration, but also the danger of hubris. Chains symbolize bondage and oppression, but also connection and strength.

The shield protects and defends, representing honor and military virtue. Mazes and labyrinths symbolize confusion, complexity, and the search for meaning in chaotic circumstances. Fortresses and castles represent security and power, but also isolation and defensiveness.

Battlefields embody conflict, struggle, and the testing of character under extreme circumstances. The throne represents ultimate authority and divine rule, but also the burden of judgment and responsibility. These symbols help literature explore themes of power, resistance, and the human cost of conflict.

Literary Techniques and Symbolic Function

Understanding how symbols operate in literature requires examination of specific techniques authors employ. Repetition reinforces symbolic meaning, as symbols gain power through recurrence and variation. Juxtaposition creates meaning through contrast, placing symbols in opposition to highlight thematic tensions.

Contextual development allows symbols to evolve throughout a work, gaining complexity as narrative progresses. Cultural layering enables authors to draw upon multiple symbolic traditions simultaneously, creating rich, multivalent imagery. Ironic subversion allows writers to challenge conventional symbolic meanings, creating new interpretations through unexpected usage.

The most powerful literary symbols operate on what critics call “archetypal levels”—they tap into fundamental human experiences and psychological patterns that transcend cultural boundaries. These symbols resonate because they connect individual narratives to universal themes of birth, growth, struggle, love, death, and transcendence.

Contemporary Relevance and Evolution

Modern literature continues to employ traditional symbols while developing new symbolic vocabularies appropriate to contemporary experience. Digital age symbolism incorporates technology, urban landscapes, and global connectivity while maintaining connections to classical symbolic traditions. Environmental consciousness has revitalized nature symbolism, while globalization has created opportunities for cross-cultural symbolic exchange.

The persistence of traditional symbols demonstrates their continued relevance to human experience50. While surface manifestations may change, the underlying human needs for meaning, connection, and transcendence that symbols address remain constant. Contemporary authors often employ traditional symbols with ironic awareness, creating layers of meaning that acknowledge both their power and their cultural construction.

Conclusion

The one hundred most powerful symbols in English literature represent a living tradition that continues to evolve while maintaining connections to humanity’s deepest concerns and highest aspirations. These symbols function as a shared vocabulary of meaning that enables communication across time, culture, and individual experience. They transform simple narratives into complex explorations of the human condition, allowing literature to serve its highest function as both mirror and lamp—reflecting human experience while illuminating pathways toward understanding.

The enduring power of these symbols lies in their ability to compress complex ideas into memorable images, create emotional resonances that transcend rational analysis, and connect individual stories to universal themes. They demonstrate literature’s unique capacity to speak simultaneously to the conscious and unconscious mind, creating experiences that inform, transform, and inspire readers across generations.

From the ancient symbols drawn from religious and mythological traditions to the evolving symbolic vocabulary of contemporary literature, these powerful images continue to enrich our understanding of what it means to be human. They remind us that literature’s greatest gift lies not in its ability to describe the world as it is, but in its power to reveal the world as it might be—full of meaning, connection, and infinite possibility for growth and transformation.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What makes a symbol “powerful” in literature?

A: A powerful literary symbol combines universal recognition with layered meanings, cultural resonance, and the ability to evoke emotional responses. The most powerful symbols operate on multiple levels simultaneously—literal, metaphorical, psychological, and archetypal—allowing them to enrich narratives while speaking to fundamental human experiences.

Q: How do cultural differences affect symbolic interpretation?

A: While some symbols carry universal meanings, cultural context significantly influences interpretation. Colors, animals, and religious symbols may represent different concepts across cultures. However, the most powerful literary symbols often transcend cultural boundaries by tapping into shared human experiences like birth, death, love, and transformation.

Q: Can new symbols emerge in contemporary literature?

A: Yes, contemporary literature continues to develop new symbols while reinterpreting traditional ones. Digital age imagery, environmental symbols, and globalized cultural references create new symbolic vocabularies. However, these often build upon or dialogue with established symbolic traditions rather than replacing them entirely.

Q: How can readers learn to recognize and interpret literary symbols?

A: Symbol recognition develops through reading widely, studying literary traditions, and understanding cultural contexts. Key indicators include repetition, emphasis, unusual description, and objects/images that seem to carry weight beyond their literal function. Effective interpretation considers both traditional meanings and specific contextual usage.

Q: Do authors always consciously choose their symbols?

A: Authors vary in their conscious deployment of symbolism. Some deliberately construct symbolic systems, while others draw intuitively upon cultural and literary traditions. The most effective literary symbols often combine conscious craft with unconscious cultural knowledge, creating imagery that resonates beyond the author’s explicit intentions.

Q: Why do religious symbols remain prominent in secular literature?

A: Religious symbols carry deep cultural significance that transcends specific belief systems. They provide a rich vocabulary for exploring themes of morality, transcendence, sacrifice, and redemption that remain central to human experience. Even secular authors draw upon this symbolic tradition because of its cultural familiarity and emotional resonance.

Q: How has symbolic interpretation changed over time?

A: Symbolic interpretation has evolved with changing cultural values, critical theories, and social awareness. Modern readers may interpret symbols differently than historical audiences, finding new meanings while maintaining connections to traditional interpretations. This evolution demonstrates the living nature of symbolic meaning.

Q: What role do symbols play in different literary genres?

A: Symbols function differently across genres. Poetry often employs concentrated, highly charged symbolism; novels develop symbols through extended narrative; drama uses visual and auditory symbols for immediate impact. Genre conventions influence both symbolic selection and interpretation methods.

Q: How do symbols contribute to a work’s enduring appeal?

A: Symbols contribute to literary longevity by creating multiple layers of meaning that reward repeated reading and reinterpretation. They allow works to speak to different generations and cultures while maintaining thematic coherence. The richest literary works often feature symbolic systems that continue to yield new insights over time.