Colonial Shadows: Tracing Imperial Legacy in Classic English Texts

The silence that greeted Fanny Price’s inquiry about the slave trade in Mansfield Park echoes through centuries of English literature—a deafening quiet that reveals as much as any spoken word. When Jane Austen crafted this moment of uncomfortable stillness around Sir Thomas Bertram’s dining table, she captured something profound about the relationship between English literary culture and imperial exploitation. This “dead silence” serves as a metaphor for how colonial violence was simultaneously central to and absent from the great works of English literature, creating shadows that continue to shape our understanding of canonical texts today.

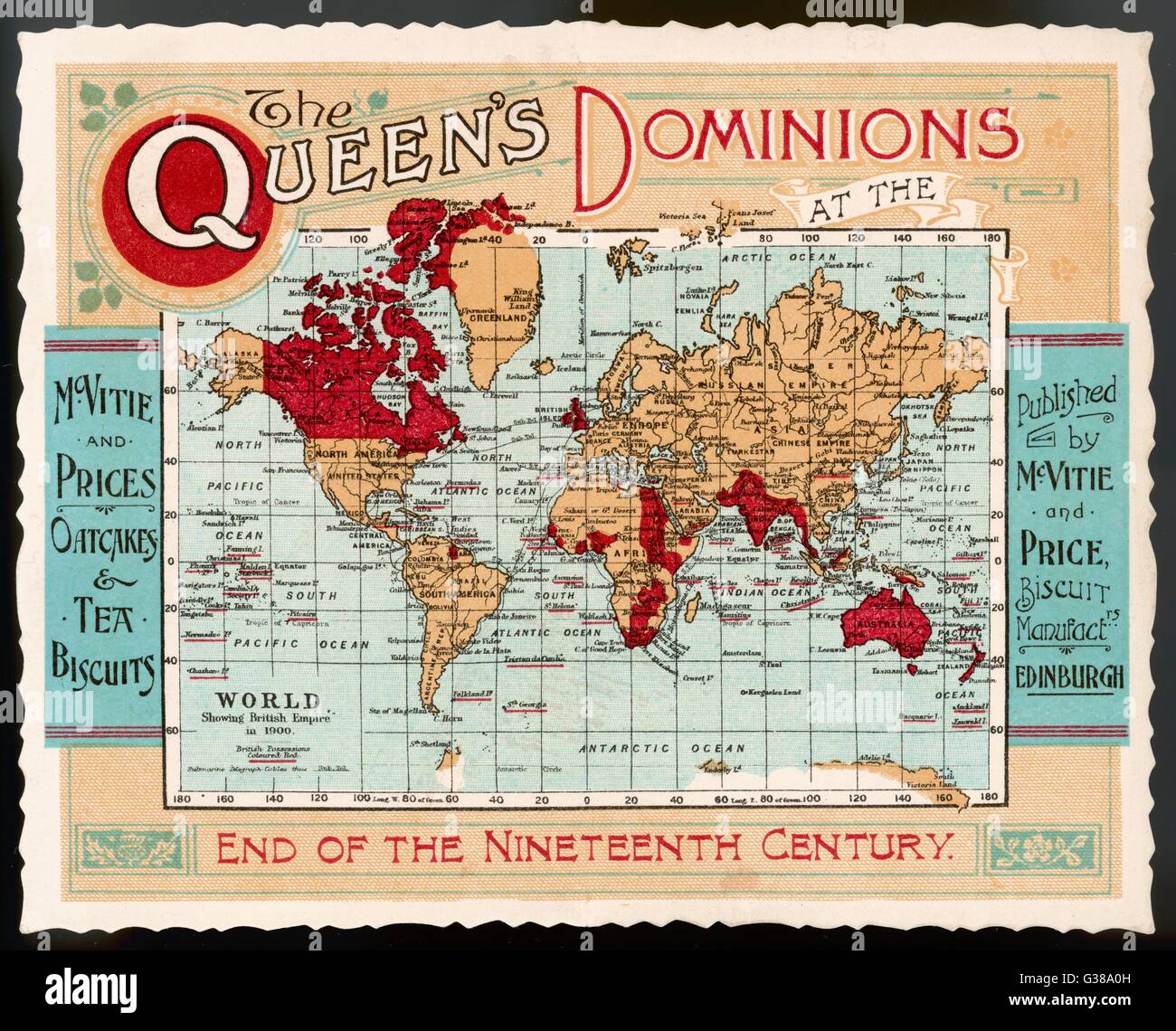

A 19th-century map highlighting the global extent of the British Empire, illustrating the vast colonial territories under British control at the century’s end

The imperial enterprise that funded drawing rooms like the Bertrams’ extended far beyond individual households—it was a global network of extraction, exploitation, and cultural domination that left indelible marks on the literary imagination. From the exotic otherness of Shakespeare’s Caliban to the mysterious darkness of Conrad’s Africa, English literature bears the traces of an empire that, at its height, controlled nearly a quarter of the world’s land mass and population. These colonial shadows manifest not only in explicit imperial themes but in the subtle ways that power, identity, and cultural difference are constructed throughout the literary canon.

The Literary Landscape of Empire

The period between 1830 and 1914 marked the zenith of British imperial power and, not coincidentally, some of the greatest achievements in English literature. This was the era when the sun never set on the British Empire, and when literature served not merely as entertainment but as a crucial mechanism for justifying and perpetuating imperial ideology. The drawing rooms where novels were read and discussed were furnished with the profits of colonial extraction—sugar from the Caribbean, tea from India, cotton from Egypt—yet this material foundation of literary culture remained largely invisible in the texts themselves.

Writers of this period operated within what Edward Said would later term “the culture of imperialism,” a vast discursive network that made imperial domination seem not only natural but necessary. The “civilizing mission” became a dominant narrative framework, positioning British intervention in distant lands as a moral imperative rather than economic exploitation. This ideological structure shaped literary production in profound ways, influencing everything from plot structures to character development to narrative voice.

The economic foundations of this literary culture were vast and varied. The East India Company, which controlled large portions of the Indian subcontinent, provided the wealth that funded country estates like Mansfield Park. The profits from Caribbean sugar plantations, worked by enslaved Africans, supported the comfortable lives of genteel families throughout England. The ivory trade that drove colonial exploitation in Africa underwrote the drawing room conversations where novels were discussed and debated. Yet these material connections remained largely invisible in literary discourse, creating what critic Edward Said calls “the structure of attitude and reference” that made imperialism seem like a natural part of the social order.

Deconstructing Colonial Discourse

Edward Said’s groundbreaking work Orientalism (1978) revolutionized our understanding of how literature participates in imperial power structures. Said demonstrated that Western representations of the “Orient”—a term that collapsed diverse cultures from North Africa to East Asia into a single, exotic other—were not neutral observations but active constructions that served imperial interests. These representations created what Said termed “imaginative geography,” a set of spatial and cultural boundaries that justified Western dominance over Eastern peoples.

Stylized collage representing Edward Said’s postcolonial critique with symbolic urban and cultural elements

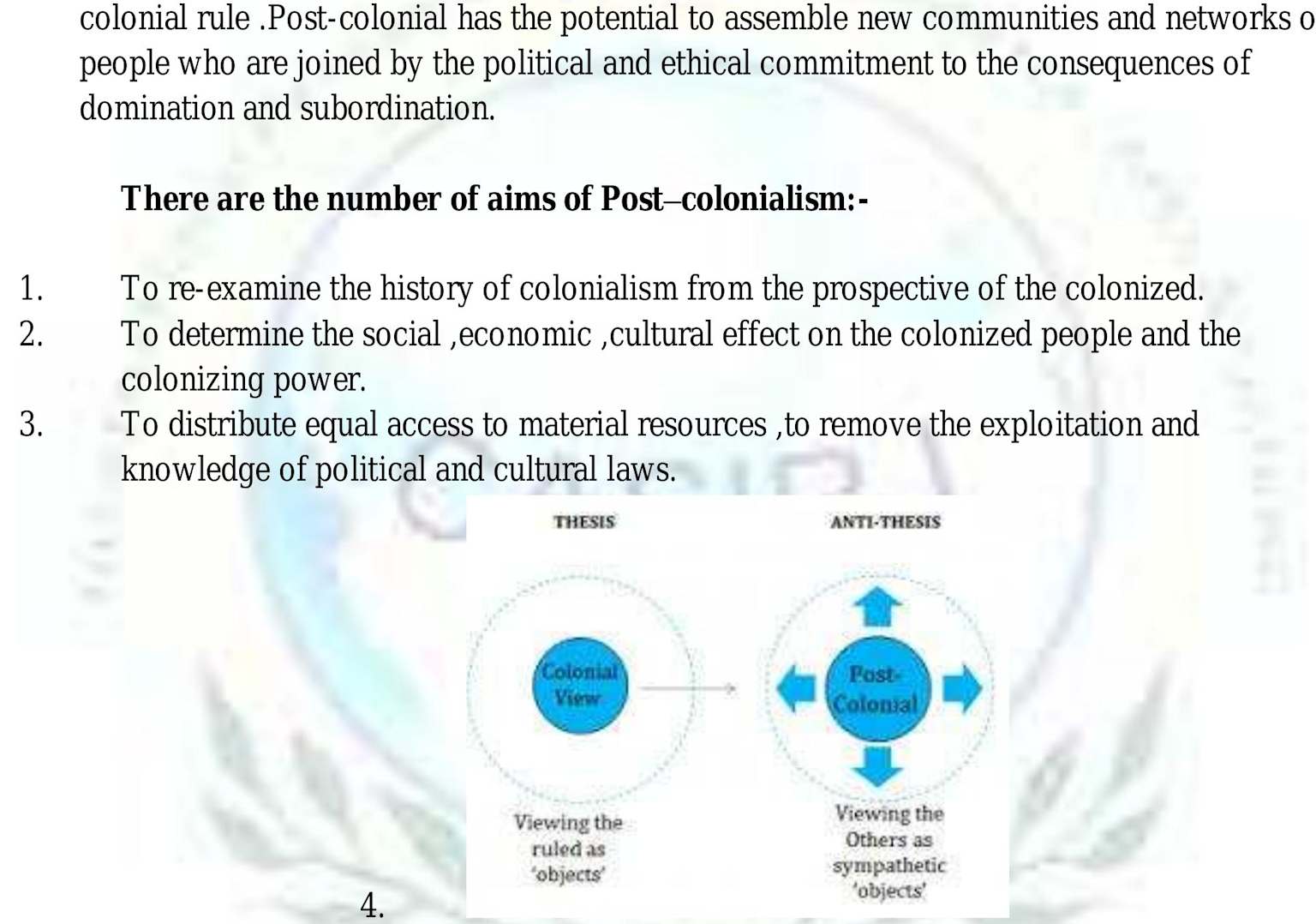

The mechanics of colonial discourse operate through what postcolonial critics call “othering”—the process of defining colonized peoples as fundamentally different from and inferior to Europeans. This othering manifests in literature through a series of binary oppositions: rational West versus mystical East, civilized Europe versus savage Africa, progressive Christianity versus backward paganism. These binaries were not simply descriptive but performative, actively constructing the identities they claimed to describe.

Language itself becomes a crucial tool of imperial power in this process. Colonial discourse employs specific linguistic strategies to establish and maintain hierarchies: the use of passive voice to obscure agency in descriptions of colonial violence, the deployment of scientific or ethnographic language to naturalize cultural prejudices, and the strategic deployment of silence to avoid uncomfortable truths about imperial exploitation. When Robinson Crusoe teaches Friday to call him “Master,” he is not simply establishing a personal relationship but participating in a broader colonial project of linguistic domination.

The representation and misrepresentation of colonized peoples in English literature follows predictable patterns that Said and other postcolonial critics have identified. Colonized characters are typically denied complex interiority, reduced to types rather than individuals, and defined primarily in relation to European protagonists. They appear as faithful servants (like Friday), exotic temptresses (like various “Oriental” women in imperial fiction), dangerous savages (like various African characters in adventure fiction), or mysterious others whose difference serves to highlight European normalcy.

Imperial Shadows in Canonical Works

The canonical texts of English literature reveal their imperial entanglements most clearly when read through the lens of postcolonial criticism. Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1899), long celebrated for its psychological complexity and innovative narrative technique, emerges as a text deeply implicated in the colonial project it appears to critique. Marlow’s journey into the Belgian Congo reveals not only the “horror” of Kurtz’s individual corruption but the systematic violence of European imperialism in Africa. Yet the novella’s critique remains limited by its inability to imagine African characters as fully human subjects rather than silent witnesses to European psychological drama.

Conrad’s famous observation that “the conquest of the earth, which mostly means the taking it away from those who have a different complexion or slightly flatter noses than ourselves, is not a pretty thing when you look into it too much” reveals both the text’s critical awareness and its fundamental limitations. The critique focuses on what imperialism does to Europeans rather than what it does to Africans, maintaining the colonial discourse’s focus on European subjectivity even while exposing imperial violence.

Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre (1847) provides another compelling example of how colonial themes operate in apparently domestic fiction. The character of Bertha Mason, Rochester’s first wife who is imprisoned in the attic of Thornfield Hall, represents what postcolonial critic Gayatri Spivak calls “the native woman as woman caught between patriarchy and imperialism”. Bertha’s West Indian origins, her racialized madness, and her ultimate destruction serve multiple narrative functions: she represents Jane’s own repressed sexuality, she embodies the threat of colonial others to English domesticity, and she must be eliminated for the English romance plot to reach its conclusion.

Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea (1966) offers a powerful postcolonial response to Brontë’s novel, giving voice to the colonial woman silenced in the original text. Rhys reveals how Antoinette (renamed Bertha by Rochester) becomes the victim of both patriarchal and colonial violence, showing how her identity is systematically destroyed by the very forces that Jane Eyre celebrates.

Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park (1814) demonstrates how colonial wealth underwrites the domestic tranquility of English country houses. Sir Thomas Bertram’s plantation in Antigua provides the economic foundation for Mansfield Park itself, yet this connection remains largely invisible in the novel’s domestic focus. The famous “dead silence” that greets Fanny Price’s questions about the slave trade represents, in Said’s reading, the novel’s broader inability to confront the violent foundations of its own existence.

Rudyard Kipling’s Kim (1901) celebrates the British imperial project in India while simultaneously revealing its dependence on surveillance, violence, and cultural domination. The novel’s protagonist, Kim O’Hara, serves as both an insider and outsider to Indian culture, allowing Kipling to romanticize imperial rule while obscuring its coercive dimensions. Kim’s participation in “the Great Game” of imperial espionage naturalizes the colonial state’s systematic monitoring of colonized populations.

Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe (1719) has been identified by postcolonial critics as a foundational text of colonial discourse. Crusoe’s relationship with Friday establishes many of the patterns that would characterize later colonial literature: the European as civilizer and teacher, the colonized subject as grateful student, and the colonial relationship as mutually beneficial rather than exploitative. Crusoe’s claim to ownership of the island—”the whole country was my own property so that I had an undoubted right of dominion”—articulates the colonial logic that would justify European appropriation of indigenous lands throughout the imperial period.

Shakespeare’s The Tempest (1611) provides an early example of colonial discourse in English literature, with the relationship between Prospero and Caliban serving as an allegory for European colonization. Prospero’s civilizing mission—teaching Caliban language and European customs—masks a relationship of domination and exploitation. Caliban’s famous lines, “You taught me language, and my profit on’t / Is I know how to curse,” reveal both the violence of cultural imperialism and the possibility of resistance through the colonizer’s own tools.

Literary Techniques of Imperial Ideology

The imperial themes in these canonical texts operate through specific literary techniques that naturalize colonial relationships and obscure their violence. Othering through characterization represents perhaps the most fundamental technique, creating characters who embody difference in ways that justify their subordination. These characters are typically denied complex psychological development, appearing instead as types that confirm European assumptions about racial and cultural hierarchy.

Geographic symbolism and exotic settings serve to create what Said calls “imaginative geography,” spatial relationships that map cultural and racial hierarchies onto physical landscapes. The mysterious East, the Dark Continent, the savage wilderness—these geographic constructions serve ideological functions, positioning Europe as the center of civilization and other regions as peripheral spaces requiring European intervention.

Narrative voice and perspective control ensures that colonial relationships are presented from European viewpoints, with colonized characters rarely granted the authority to tell their own stories. Even when colonial subjects speak, their voices are typically mediated through European narrators who interpret and contextualize their words. This narrative control extends to the broader question of who gets to represent whom, with European authors claiming the authority to speak for colonized peoples.

Absence and silence serve as colonial strategies in these texts, allowing authors to acknowledge colonial relationships while avoiding their more troubling implications. The “dead silence” in Mansfield Park represents a broader pattern of strategic omission that characterizes colonial discourse. What is not said often reveals as much about colonial ideology as what is explicitly stated.

Gothic elements frequently appear in imperial fiction, creating an aesthetic of mystery and terror that obscures the systematic nature of colonial violence. The gothic mode allows authors to present colonialism as an encounter with the supernatural or the irrational rather than as a political and economic system. This gothic imperialism, as critic Patrick Brantlinger terms it, transforms the violence of colonial exploitation into aesthetic experience.

Diagram contrasting colonial and post-colonial views alongside key aims of postcolonialism

Contemporary Critical Approaches

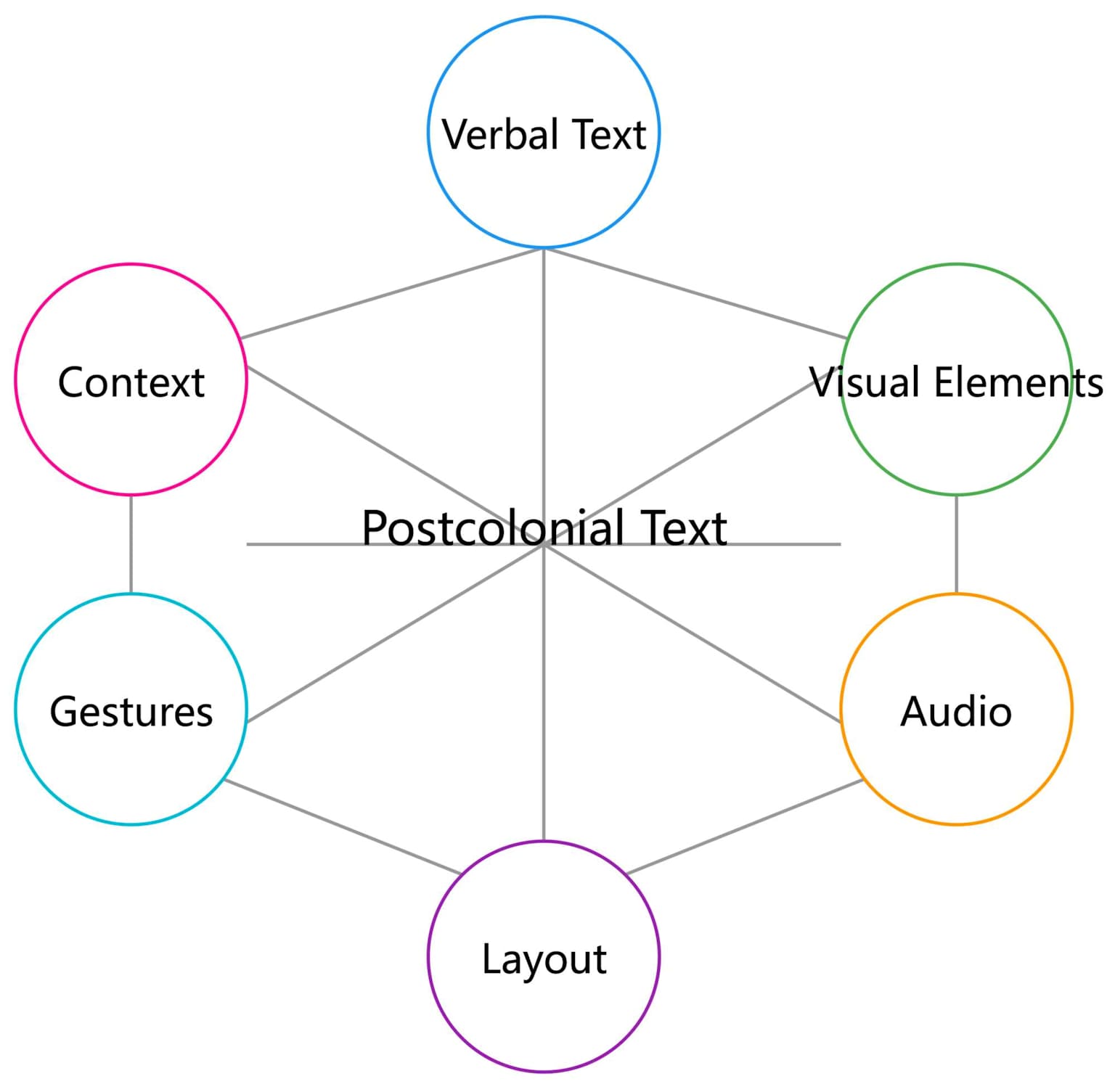

Postcolonial literary criticism has developed sophisticated methods for reading the imperial legacies in canonical texts. Postcolonial reading strategies focus on recovering the voices and perspectives that colonial discourse suppresses or marginalizes. These approaches ask not only what texts say about colonial relationships but what they silence, not only how they represent colonized peoples but how they fail to represent them.

Feminist postcolonial criticism examines the particular ways that colonial and patriarchal oppression intersect in the lives of colonized women. Critics like Gayatri Spivak have shown how colonized women face what she calls “double colonization,” oppressed both as colonized subjects and as women within patriarchal societies. This approach reveals how texts like Jane Eyre participate in both imperial and patriarchal ideology.

Contrapuntal reading methods, developed by Edward Said, involve reading canonical texts alongside the histories and perspectives they exclude. A contrapuntal reading of Mansfield Park would consider not only Austen’s domestic plot but also the experiences of enslaved people on Sir Thomas Bertram’s plantation. This method reveals the global dimensions of apparently local stories.

Decolonizing the literary canon involves both critique of existing texts and recovery of suppressed voices and perspectives. This work includes not only postcolonial readings of canonical authors but also the recovery and promotion of texts by colonized and formerly colonized peoples. Writers like Jean Rhys, Chinua Achebe, and Salman Rushdie have created powerful responses to colonial discourse, “writing back” to the imperial center.

Colonial Legacies in Modern Literature

The colonial shadows traced in classic English texts continue to influence contemporary literature in complex ways. Contemporary postcolonial responses include direct revisions of canonical texts (like Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea) as well as broader projects of cultural recovery and reinvention. These texts often employ what postcolonial critic Bill Ashcroft calls “post-colonial writing techniques”: linguistic experimentation, narrative fragmentation, and cultural hybridity that challenges the assumptions of colonial discourse.

Rewriting and revision projects have become a significant subgenre of contemporary literature, with authors from formerly colonized countries offering alternative perspectives on canonical texts and historical events. These projects reveal how colonial discourse continues to shape literary and cultural production even in postcolonial contexts.

Ongoing scholarly debates in postcolonial criticism focus on questions of representation, authority, and the politics of literary study. Critics continue to debate the effectiveness of different reading strategies, the relationship between literary analysis and political action, and the role of literature in ongoing processes of decolonization.

Educational implications of postcolonial criticism have been significant, leading to curricular reforms that challenge the exclusive focus on European and American literature. These changes reflect broader questions about whose voices and perspectives should be included in literary education and how to teach canonical texts in ways that acknowledge their imperial entanglements.

Diagram illustrating components of postcolonial text analysis including verbal, visual, audio, contextual, gestural, and layout elements

Conclusion

The colonial shadows that haunt classic English texts reveal the complex relationship between literature and empire that shaped centuries of cultural production. From the strategic silences of Mansfield Park to the gothic horror of Heart of Darkness, from the exotic otherness of The Tempest to the civilizing mission of Kim, these texts bear the traces of an imperial project that was always both material and cultural, both economic and ideological.

Understanding these colonial legacies requires more than simply identifying imperial themes in literary texts—it demands a fundamental reconsideration of how meaning is constructed, whose voices are heard, and what assumptions about culture, race, and power underlie literary expression. The postcolonial critical approaches developed by scholars like Edward Said, Gayatri Spivak, and others provide essential tools for this work, revealing how colonial discourse operates not only in explicitly imperial texts but in the broader structures of literary and cultural authority.

The relevance of this analysis extends far beyond academic literary study. In an era of ongoing global inequality, cultural conflict, and debates about historical memory, understanding how literature has participated in imperial projects remains crucial for developing more equitable forms of cultural expression and exchange. The colonial shadows in classic English texts remind us that literature is never innocent of the power relations that shape its production and reception, and that reading responsibly requires constant attention to whose voices are included and whose are marginalized.

As we continue to grapple with the legacies of colonialism in contemporary culture, the work of tracing imperial shadows in literary texts becomes not merely an academic exercise but a form of cultural and political engagement. By understanding how colonial discourse has shaped literary expression, we create possibilities for more inclusive and equitable forms of cultural production that acknowledge the full complexity of our shared global history.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What is colonial discourse in literature?

Colonial discourse refers to the system of knowledge, language, and representation that Europeans used to describe and control colonized peoples and territories. In literature, this discourse manifests through stereotypical representations, hierarchical cultural assumptions, and narrative techniques that naturalize imperial domination.

Q: How did the British Empire influence English literature?

The British Empire profoundly influenced English literature by providing economic foundations for literary culture, shaping narrative themes and character types, and creating ideological frameworks that justified imperial domination. Imperial wealth funded the leisure class that produced and consumed literature, while colonial encounters provided exotic settings and cultural conflicts that drove many literary plots.

Q: What is Edward Said’s theory of Orientalism?

Said’s Orientalism argues that Western representations of the “Orient” were not neutral observations but constructed images that served imperial interests. These representations created binary oppositions between rational West and mystical East, civilized Europe and backward Asia, that justified European domination over Eastern peoples.

Q: Which classic English novels contain colonial themes?

Major texts include Heart of Darkness (colonial exploitation in Africa), Jane Eyre (West Indian colonial wife), Mansfield Park (plantation slavery), Kim (British India), Robinson Crusoe (colonial prototype), and The Tempest (early colonial allegory). These themes often operate subtly rather than explicitly.

Q: How do postcolonial critics analyze Victorian literature?

Postcolonial critics use techniques like contrapuntal reading (reading texts against suppressed histories), discourse analysis (examining language and power), and recovery work (restoring marginalized voices). They focus on how texts construct cultural difference, justify imperial relationships, and participate in broader colonial projects.

Q: What literary techniques were used to justify imperialism?

Key techniques include othering through characterization, exotic geographic symbolism, narrative perspective control, strategic silences about colonial violence, and gothic aestheticization of imperial encounters. These techniques make imperial relationships seem natural rather than constructed.

Q: How has postcolonial criticism changed literary studies?

Postcolonial criticism has challenged the exclusive focus on European and American literature, developed new reading methodologies, recovered suppressed texts and voices, and revealed the political dimensions of literary representation. It has fundamentally altered how we understand the relationship between literature and power.

Q: What is the significance of ‘othering’ in colonial literature?

Othering creates hierarchical relationships between colonizer and colonized by representing cultural difference as natural inferiority. This process justifies colonial domination by making it seem that colonized peoples require European guidance and control. Literature participates in othering through characterization, narrative voice, and cultural representation.

Q: How do contemporary authors respond to colonial literary legacies?

Contemporary postcolonial authors employ strategies like “writing back” to canonical texts, linguistic experimentation, cultural hybridity, and historical revision. Examples include Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea (responding to Jane Eyre) and Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart (countering Heart of Darkness). These works challenge colonial discourse by centering previously marginalized perspectives