What Is English Literature? Exploring the World of Words and Imagination

English literature is more than a shelf of beloved books; it is a vast record of how Anglophone writers have wrestled with power, faith, beauty, and belonging for almost 1,600 years123. From an anonymous scop chanting Beowulf in an Anglo-Saxon hall to contemporary poets confronting climate crisis, the tradition maps both the outer facts of history and the inner life of the mind. This post traces that story, highlights defining themes and techniques, and offers practical ways to read critically—equipping enthusiasts, students, and educators to navigate the ever-expanding landscape of English letters.

Defining English Literature

Scholars debate whether “literature” can ever be fixed by genre, style, or social prestige. Britannica stresses the body of written works in English—no matter where produced—as the simplest definition. Cultural theorist Terry Eagleton counters that the label is always provisional, applied to texts a society happens, for ideological reasons, to prize at a given moment. Between those poles, most classrooms frame English literature as imaginative writing—poetry, drama, and prose—valued for aesthetic power, linguistic innovation, and enduring insight1011.

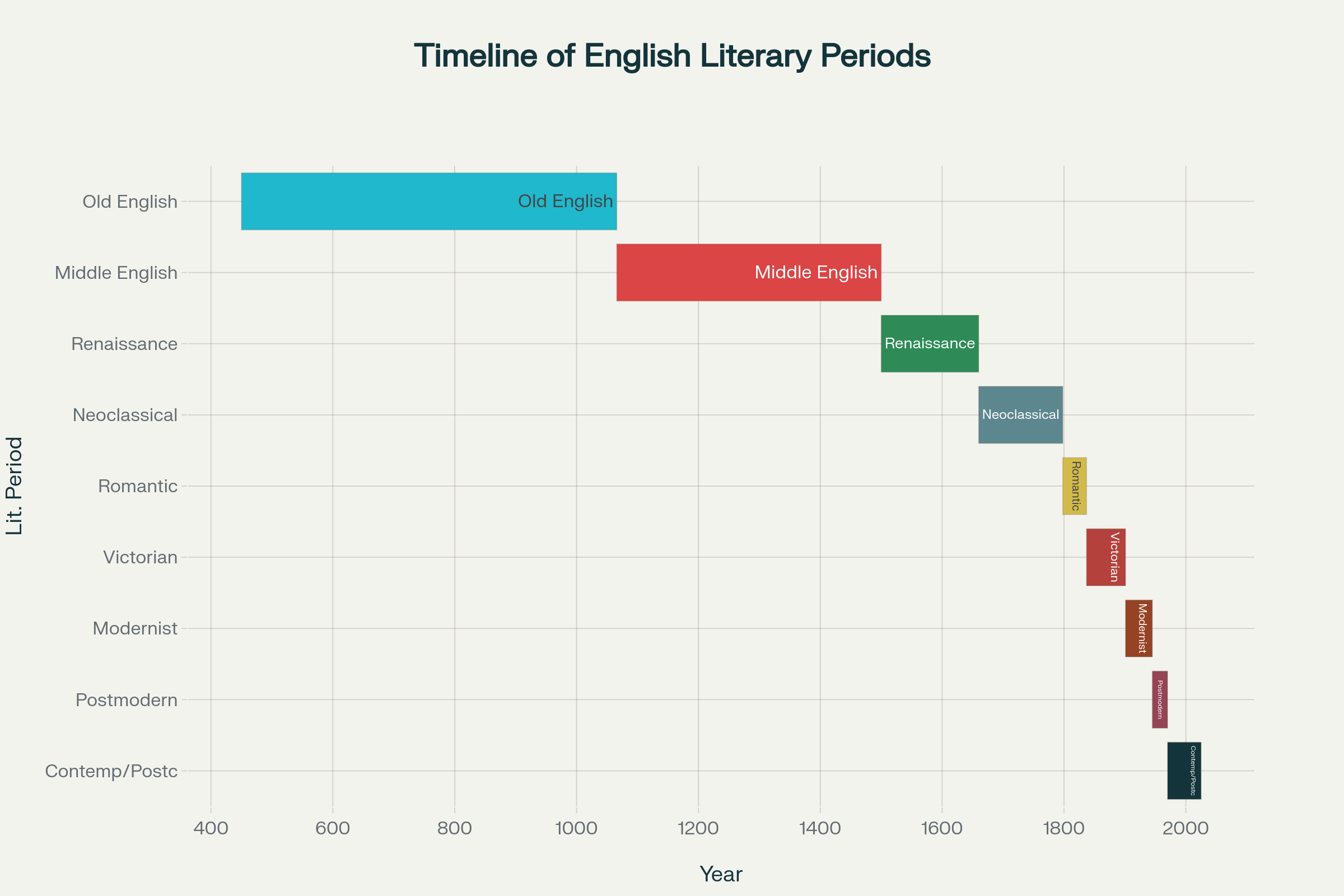

A Brief Chronological Journey

English literary history is often organised into overlapping periods, each shaped by distinct linguistic, political, and artistic forces.

Old English (c. 450 – 1066)

The earliest surviving masterpiece, Beowulf, combines pagan heroics with Christian fatalism in 3,182 alliterative lines. Its monster-slaying plot explores reputation, communal duty, and the fragility of human glory—motifs that echo throughout later epics.

Middle English (1066 – 1500)

After the Norman Conquest, French and Latin mingled with Anglo-Saxon to create Middle English. Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales popularised the vernacular by staging a pilgrimage where multiple social ranks trade stories about desire, piety, and deceit. Chaucer’s vivid frame narrative forecasts the novel’s polyphonic possibilities.

Renaissance to Neoclassical (1500 – 1798)

The Renaissance heralded a surge of humanist inquiry, blank verse, and rhetorical flourish. William Shakespeare probed ambition and identity in lines such as “All the world’s a stage” (As You Like It). The subsequent Neoclassical age prized order, wit, and satirical bite, exemplified by Pope’s heroic couplets and Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, responding to Enlightenment rationalism.

Romantic and Victorian (1798 – 1901)

Romantic writers privileged emotion, nature, and the rebel imagination. William Wordsworth found the “still, sad music of humanity” in mountains and memory. The Victorian period confronted industrial upheaval; novelists like Charles Dickens exposed urban poverty and class conflict in works such as Oliver Twist and Hard Times.

Modernist to Postmodern (1901 – 1970)

World-war trauma fractured previous certainties, ushering in Modernism’s experimental forms. T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land stitches mythic and contemporary fragments to depict spiritual drought. Virginia Woolf advances stream of consciousness, revealing thought’s nonlinear drift in Mrs Dalloway and To the Lighthouse. Post-1945 Postmodern writers embraced irony and metafiction, questioning whether grand narratives remain possible.

Contemporary / Postcolonial (1970 – present)

Recent decades spotlight voices from former colonies interrogating empire’s legacies. Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart uses Igbo proverbs and potent symbolism—yams, locusts, fire—to dramatise cultural rupture under British rule. Today, diasporic, queer, eco-critical, and digital texts keep expanding the canon’s borders.

Recurring Themes in the English Canon

| Theme | Early Instance | Later Resonance |

|---|---|---|

| Heroism & mortality | Beowulf’s quest for lasting fame14 | Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings reworks Anglo-Saxon courage1 |

| Nature & the sublime | Wordsworth’s “sense sublime” in Tintern Abbey | Contemporary eco-poetry confronting climate anxiety |

| Social justice | Dickens on industrial squalor | Postcolonial fiction exposing neocolonial power |

| Alienation & fragmentation | Eliot’s sterile cityscape | Postmodern narratives of digital isolation |

Techniques That Shape Literary Experience

Symbolism

A symbol is a concrete image that evokes ideas beyond its literal identity—“writings having excellence of form…expressing ideas of permanent interest”. Fire in Things Fall Apart captures Okonkwo’s volatile masculinity; the green light in The Great Gatsby signals unattainable desire. Mastering symbolism deepens thematic layers and rewards close reading.

Stream of Consciousness

Critical lenses—from Marxist to postcolonial—reveal how texts negotiate power and ideology4936. Cambridge’s pioneering practical-criticism method asks students to focus first on language, then radiate outward to biography and history1254. Today’s classrooms blend close reading with archival research, media adaptation, and digital annotation, underscoring that literature is a living dialogue between past and present.

Conclusion

English literature endures because it couples artistic surprise with emotional truth. Each era re-imagines inherited forms to confront new realities—whether Viking raids, steam engines, world wars, or globalisation. By tracking its periods, themes, and techniques, readers gain not only academic insight but also a richer awareness of how stories shape—and are shaped by—the human imagination1136.

FAQ: Quick Answers for Curious Readers

1. Why does English literature include American, Indian, or Nigerian texts?

Because the term refers to language, not geography; any work written primarily in English can enter the conversation13637.

2. What’s the difference between Old English and modern English?

Old English (Beowulf) is a Germanic tongue barely intelligible to modern speakers, while contemporary English has evolved through Norman French, Latin, and global borrowings141513.

3. How do I start analysing a poem?

Begin with sound and imagery, identify key symbols, then relate them to the speaker’s tone and historical context115544.

4. What defines Romantic poetry?

Emphasis on emotion, nature, individual vision, and rebellion against industrial rationalism—epitomised by Wordsworth and Coleridge225623.

5. Why is The Waste Land considered difficult?

Its collage of voices, myths, and languages mirrors post-war fragmentation; Eliot’s own endnotes hint at the dense allusions293130.

6. Are Dickens’s novels still relevant?

Yes; his social critiques of poverty, child labour, and urban overcrowding echo in current debates on inequality and industrial ethics252627.

7. What is postcolonial literature?

Writing that responds to colonial histories, asserting cultural identity and exposing ongoing power imbalances—works by Achebe, Rushdie, and Kincaid are key examples354236.

8. How does symbolism differ from allegory?

A symbol is a single image with layered meaning; an allegory is an extended narrative in which each element systematically corresponds to a second level of signification434411.

9. Can contemporary genre fiction count as “literature”?

If it wields language artfully and engages enduring questions, yes—literary value is fluid and continually renegotiated by readers and critics479.

Dive into any period, follow the symbols, listen to the voices—and you will find English literature a boundless realm where words keep remaking the world.